For some patients suffering from a chronic disease, giving their condition a name, be it “Rosy”, “the Green Lady”, or “my best friend”, helps them live with it more easily.

Sometimes I feel like I know Pamela better than my own mother!” It’s hard to know if Eric (name has been changed) is joking when he shares this titbit. The 23-year-old is living with cystic fibrosis, and the disease has set the pace of his life since childhood. He refers to it as Pamela, a woman’s name that calls to mind bleach-blond hair and California beaches. “Five years ago, I found myself watching a show on TV that was featuring series from the 1990s. When that blond lady in the red swimsuit started running on the sand (editor’s note: Pamela Anderson, leading actress from the series Baywatch), it was like an epiphany. Don’t ask why...” Ever since, the young man almost always uses the name to refer to his disease – at least, with his family. “In the beginning, my parents and friends looked at me a bit strangely when I’d say things like ‘Pam is still sleeping this morning’ or ‘Pamela is really not in a good mood today’. But they got used to it. Now, they’re the first ones to ask me about how my ‘girlfriend’ is doing!”

By giving his cystic fibrosis a name, Eric successfully navigated a challenge that many patients living with a serious disease struggle to manage – namely, the issue of describing a condition that lasts for months, years, or even an entire lifetime and adapting to such a life-altering reality. Eric is not an isolated case. Online health forums are full of people living with cancer, multiple sclerosis, or severe diabetes who talk about “Mark”, “the Green Lady”, or “my Faithful Companion” on a daily basis. “This down-to-earth approach to disease, in which a patient personifies their condition and establishes a relationship with it, is mostly seen in chronic patients” says Francesco Panese, a professor of medical social studies at Lausanne University (UNIL). He goes on to explain that this isn’t a new phenomenon. “It seems cultures have always considered diseases as separate entities, with their own wills and personalities. This idea was undermined by modern western medicine, which started to take shape in the nineteenth century.”

“However, anthropologists have observed that people continue to think of disease in the same informal terms. You can think of it as a subjective way of trying to cope” explains the sociologist.

Patients often say their disease must be both treated and respected for this coexistence to function properly. Naming it helps forge a truce while also enabling the patient to give meaning to the challenge that lies before him or her. Indirectly, the patient’s quality of life can improve as a result because “we typically feel better when we give meaning to our disease”.

In some patients, this same need can manifest itself in other ways, such as by “trying to know everything about the disease to take control of their anxiety”. Francesco Panese notes that modern society is more accepting of the complementary nature of an approach that blends medicine and the mundane: “In the 1960s, a doctor might have laughed if a patient referred to their disease by name.”

Patients aren’t just naming their conditions. Other components related to the disease, especially treatments and medical equipment, can be christened as well. On her blog, “My Life with EDS”, a young Belgian woman with Ehlens-Danlos (EDS) syndrome explains that she calls Lévocarnil “my little Levovo” and baclofen “Bacloclo”. To talk about her physical therapy sessions, she says she’s “going to see Harry”, and when it’s time for hydrotherapy, she “heads to the pool”. As for her bottle opener, she calls it “Canari”. The blogger explains that her use of nicknames “came pretty naturally” without any conscious effort on her part, and that the trick makes her day-to-day life “so much better”.

During her research into the impact of HIV treatments on patients’ lives, Noëllie Genre, a PhD candidate at UNIL’s Social Science Institute, also noticed that people tended to personify their treatments. “At the start of their treatment, some patients refer to the medicine as a bomb. Over time, however, they establish a relationship with it by creating a more familiar frame of reference.” Genre gives a few examples of terms she’s heard during her interviews, including “the friend I see every day”, “my buddy”, or even “my best friend”.

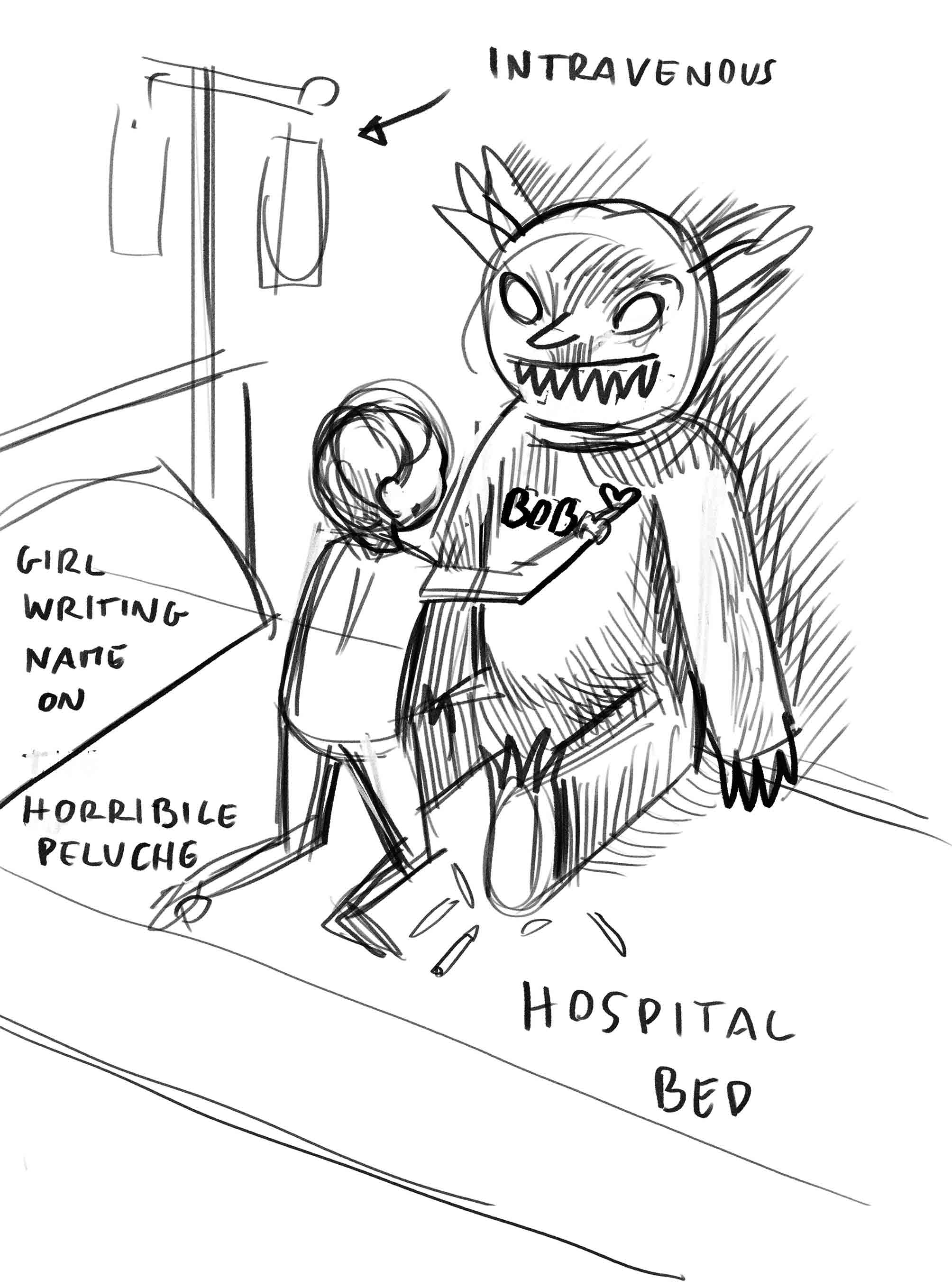

Italian illustrator Marco Melgrati explored several possibilities to illustrate this topic.

In addition to the names some patients give to their disease or treatment, there is another category of names that is much more standardised. These terms are used to refer to behavioural disorders, and eating disorders in particular. The vast majority of young anorexic women from Generation Y and Z use the name “Ana” when speaking about their condition, while women from the same group talk about “Mia” when referring to bulimia. Male names include “Skip”, meaning schizophrenia, and “Owen”, or obsessive compulsive disorder (see box). These names became standardised in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when massive communities focused on eating disorders started forming online. Major internet providers were worried about the trend and started to censure the use of the terms “anorexia” and “bulimia”. “Ana” and “Mia” were invented to get around the restrictions. Today, an online search for these names will yield hundreds of blogs and forums dedicated to eating disorders. “Sometimes, it’s easier to say ‘Ana is such a pain in the ass. I want to throw her out the window’ than ‘I want to get better’, because it’s easier to take action against someone else than against yourself,” says the author of the blog Mia-solitude. ⁄

In 2015, Marine Barnérias was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at the age of 21. Rather than feel sorry for herself, the university student decided to live out her dream of going on a long trip to far-flung corners of the world. For eight months, she travelled solo with her backpack through New Zealand, Myanmar, and Mongolia. During the first part of her trip, the young French woman called her MS “Rosy”. For her, she thought of it as a way to give a pretty name to something that was very ugly.

In doing so, she freed herself from a part of the burden of her disease. Barnérias decided to tame Rosy and travel with her to their next adventure. One of these trips became a book, Seper Hero, that was published this year by Flammarion. The title refers to the French acronym for MS: SEP.

Names usually associated with certain behavioural disorders

Anorexia

Ana/Rex

Bulimia

Mia/Bill

Depression

Deb/Dan

Self-

mutilation

Cat/Sam

Paranoia

Perry/Pat

Insomnia

Izzy/Isaiah

Schizophrenia

Sophie/Skip

Anxiety

Annie/Max

Suicide

Sue/Dallas

OCD

Olive/Owen