Should patients be kept alive against their will? Is assisted suicide defensible? The philosopher, and former French Minister of Youth, Education and Research, sounds off on euthanasia.

«Faut-il légaliser l’euthanasie?» Axel Kahn and Luc Ferry, published by Odile Jacob, 2010

In Vivo Public opinion is divided on the questions of euthanasia and therapeutic obstinacy. What is your position in this regard? Luc Ferry The concept of “dying with dignity” seems very fragile to me, not to mention that it often carries very distressing connotations. It seems to imply that human dignity is related to autonomy, and that such dignity can be lost through the extreme mental and physical dependence that old age and illness can sometimes thrust upon us. Quite frankly, I find the idea of drawing any equivalence whatsoever between “dependence” and “indignity” to be morally intolerable, as if a human being could “lose his dignity” on account of being weak, ill, old, and why not ugly, for that matter, and therefore thrust into a situation of extreme dependence. My question is: can a human being ever lose his dignity in such a way? He can probably lose it in another way, by becoming a scoundrel, but certainly not by being weak and dependent.

IV You then argue in favour of respect for life, whether or not it is difficult. LF I argue for a patient’s absolute right to even the most extreme form of dependence and weakness, in addition to the necessity, in such cases, of advocating understanding and support, even love, rather than trying to make others understand that it is better to make a clean sweep and stop bothering the world…

More generally, one could hope that society would stop being encouraged to consider old age as an “illness” that responds only to two treatments: DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone, a hormone known for its anti-ageing effects, earning it the nickname of “the hormone of youth”, editor’s note) to begin with, and euthanasia to end with… I would say the same thing to “pro-suicide” arguments: the very notion of assistance indicates that we are not dealing with the exercise of a purely individual freedom. Assistance implies a relationship with others. Suicide supporters focus on the request for assistance and the guarantees offered by checking the merits of said request. However, by focusing mainly on the request, we almost forget the other half of the agreement: the answer to such a call for help. Far from arguing in favour of the ideal individual autonomy that all supporters of assisted suicide hold sacred, the truly desperate appeal on the other party shows that, in this case, the person making the appeal is essentially dependent – since he would otherwise simply commit suicide without assistance. As a result, it is the ethical problem of the answer provided which must be considered essential, and not the obsessive checking of the quality of the request. Who can claim in all certainty that death is the right answer to a call for help? Allow me at least to doubt it. We only have to think about those we love to shudder at the idea that they could, one desperate day, fall in the hands of those terrible doctors delivering the quick and painless “exit”…

IV But hospitals are not for desperate people, rather patients at the end of their lives… LF That is not true today: these clinics end the lives of people in perfect physical health who are only, as they say, “tired of life”. They are mostly the elderly, both men and women… But what proves to us that a lonely and slightly depressed old lady has more freedom to desire death than a young girl who is struggling to get over her cheating fiancé? So much has been said and done to make us think of the elderly person as useless, a burden, a piece of rubbish, less attractive and less independent than before; in short, undignified!In the end, the patient has no other choice but to die with this famous “dignity”, which ultimately becomes another word for indifference.

IV So, where is the dividing line? LF In any case, it is not merely a question of age, that would be absurd! The truth is that human dignity is not a quantitative question; it does not form part of the scale by which one measures – how, exactly? – pleasure and pain. The human being has something which surpasses the mere man: a certain transcendence that forces respect and deserves to be fought for. Some might say that this premise cannot be proven. Perhaps, as is always the case in matters of morality, which is not an exact science. But if I had to choose between a so-called humanitarian act consisting of killing and another consisting of saving and loving, you will forgive me for choosing the second option.

“We must stop considering old age as an illness.”

IV You have had the opportunity to work with many health professionals on the issue of therapeutic obstinacy. What struck you most during your discussions? LF Surveys conducted among doctors from some twelve Western countries show that over 40% of them admit to having been faced with euthanasia requests. Nobody knows how many responded favourably, but at a minimum, these figures show that the practice of euthanasia could easily become standard. What struck me most? First and foremost, the real and prevailing concern for humanity among health professionals, followed by their lack of a reliable reference framework for making decisions and, as a result, their request for clarification of all the different positions taken…

IV You often talk about different views on therapeutic obstinacy, which are necessary to understand requests from families. LF Yes. The first position is the one held by religions, which are mostly all hostile to euthanasia, all the more to assisted suicide, and also to therapeutic obstinacy. However, their definition of the latter is highly minimalist. Why? Because they are much more hostile to euthanasia than to therapeutic obstinacy and the two problems are related like two sides of the same coin.

IV Do you have any examples? LF For one, there is the Catholic Church, which has always been most radically opposed to euthanasia in all forms. The Church bases its position on a simple principle (which, moreover, should have opposed it equally to the death penalty, to which it has nevertheless always been favourable). This principle is expressed very clearly in paragraph 2280 of the official Catechism of the Catholic Church: “We are stewards, not owners, of the life God has entrusted to us. It is not ours to dispose of.” The Church naturally distinguishes between active euthanasia, which it strictly rejects, and the legitimate refusal of therapeutic obstinacy. However, “leaving to die” is only justified in extreme borderline cases, such that the decision to stop treatment may be very difficult to define in practice.

IV Illness also plays a unique role in this case. LF Most definitely. On the one hand, the illness could be a “road of conversion”: it can, once again according to the “Catechism”, “make a person more mature, helping him discern in his life what is not essential so that he can turn toward that which is. Very often illness provokes a search for God and a return to him.” The typically modern ideal of a quick and gentle death, if possible in a state of unconsciousness, is therefore not that of the Church which is keen to remind us how, in ancient times, people were less afraid of death than of what was supposed to follow it, such that the agony, far from being cut short, was an opportunity to make peace with oneself, others and God.

On the contrary, it is an altruistic theory whose supreme principle could be expressed as follows: an action is good when it strives to achieve the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest possible number of beings concerned by the action.

IV What other views of therapeutic obstinacy would you mention? LF That of utilitarianism, which is nearly completely predominant in the Anglo-Saxon world. According to these views, therapeutic obstinacy begins with the refusal to meet a patient’s request for euthanasia or assisted suicide.

IV Where does this idea come from, which is radically different from the previous one? LF It should be remembered that, contrary to what the French word suggests, utilitarianism is not a doctrine which glorifies selfishness and the pursuit of private interests. On the contrary, it is an altruistic theory whose supreme principle could be expressed as follows: an action is good when it strives to achieve the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest possible number of beings concerned by the action. Once this has been clarified, we can understand that based on such premises, utilitarianism not only justifies euthanasia, but also justifies any form of opposition to therapeutic obstinacy: to the extent that utilitarianism entails a “calculation of pleasures and pains”, it goes without saying that, from the moment when a life consists of infinitely more pain than pleasure, without the possibility of foreseeing the slightest improvement in the future, action must be taken and recourse to euthanasia granted as soon as the patient clearly requests it.

IV In that case, is there no ideal approach to illness and death? LF Certainly not! As you can see, these positions are completely irreconcilable. For example, there is no practical way of balancing the demands of a fundamentalist Catholic family with those of a medical establishment converted to utilitarianism, and vice versa. We are forced to proceed by trial and error, to navigate the pitfalls and try to understand the logic motivating all parties. Why? Because there are highly divergent philosophical and religious positions and none of them can seriously claim to prevail over the others – that is why I am always dubious of strict legislation on the subject. ⁄

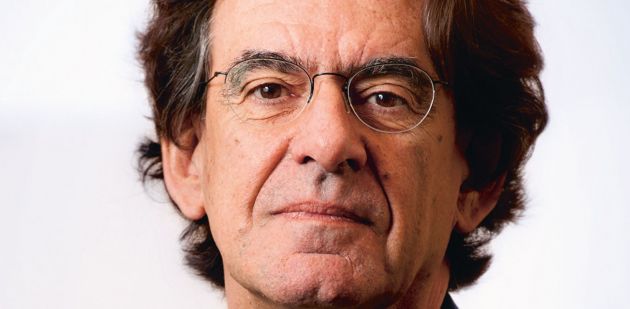

Born in 1951, Luc Ferry studied philosophy and political science. He has written several books, in particular The new ecological order, translated into 15 languages and for which he was awarded the Prix Medicis and the Prix Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His initially discreet career entered the fast track in 2002 upon his appointment as French Minister of Youth, Education and Research. He is currently Chairman of the conseil d’analyse de la société français (CAS – French society analysis council).

“Who can claim in all certainty that death is the right answer to a call for help? Allow me to doubt it. We only have to think about those we love to shudder at the idea that they could fall in the hands of those terrible doctors delivering the quick and painless “exit”…”