Telemedicine has transformed healthcare by breaking down distance barriers. And the revolution has only just begun.

Jul 16, 2014

In the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region in France, hospitals have set up a telemedicine solution to act as quickly as possible in the event of a stroke. Patients experiencing a stroke can now be evaluated remotely by a neurologist if one is not available at the hospital where they are located. This measure is expected to save lives, as every minute counts to reduce the risk of death and damage when a stroke occurs.

It’s 7 September 2001. A patient at Strasbourg University Hospitals has just undergone a successful gallbladder removal. Though a common procedure, there was something strikingly different this time: the surgeon was over 6,000 kilometres away and performed the operation using a robot named Zeus. The “Lindbergh operation”, and others like it, helped propel medicine into a new era.

Fast-forward twelve years. Medical practices in all disciplines have changed radically worldwide, spurred by improvements in the mobility and computing power of telemedicine terminals and by the ready availability of high bandwidth. Doctors can use telemedicine for a host of functions, for instance to perform remote consultations, share expertise with colleagues, and send and interpret a patient’s parameters. The technology has plenty of applications in various procedures and treatments, both routine and complex, from video-conferencing to robotic surgery.

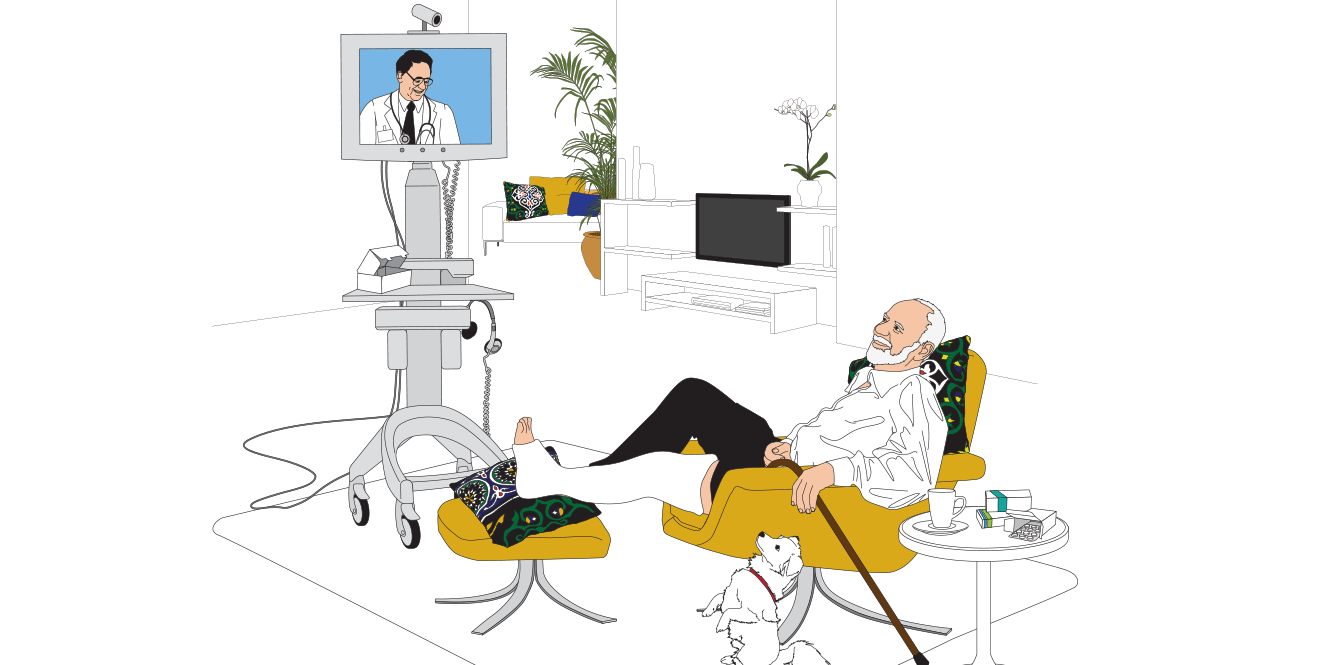

Telemedicine technology also spares elderly and disabled patients from having to travel to see a doctor in person. “Patients are equipped with mobile devices that send information to healthcare professionals, who monitor their state,” says Alain Junger, head of IT systems in the Healthcare division at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). “We can respond to their questions and concerns without their having to come to the hospital, and we can react swiftly if need be.” In the same vein, the technology prevents patients who are recovering from an operation or long-term illness from having to make numerous exhausting – and expensive – trips back and forth.

Telemedicine saves precious minutes for people who live far from a stroke centre.

Speedy high-tech reactions

“New technologies are having a huge impact on our daily lives, especially in nursing,” says Alain Junger. “The CHUV has lots of telenursing tools used to care for hospitalised patients.” Doctors and nurses can now monitor screens that continuously display not only patients’ standard vitals, such as heart and respiratory rates and blood pressure, but also their oxygen saturation. The screens also show the patient’s position and whether he or she is moving.

These new tools allow doctors to react faster, which is especially critical in emergency medicine. “The time window for treating a stroke is narrow,” says professor Mikael Mazighi of the Neurology Service at the Bichat hospital in Paris. “Once the first symptoms appear, we have only four-and-a-half hours to start intravenous thrombolysis. A stroke victim’s brain loses two million neurons each minute, so it is essential to act quickly and open the cerebral artery blocked by a clot.” The problem is that this procedure can only be prescribed by a neurologist. Telemedicine saves precious minutes for people who live far from a stroke centre. The emergency doctor contacts the neurologist, who examines the patient by camera, orders the clinical examination, reviews the CAT-scan or MRI and decides on the appropriate treatment, which is then administered on site.

Alain Junger sees limitless technical possibilities across the board. “The spread of high bandwidth and the development of nanotechnology are creating new possibilities by the day,” he says.

In Mali in 2012, 2,000 people benefited from scans that were interpreted remotely. The procedures were led by RAF T, the Telemedicine Network for Francophone Africa, developed by Geneva University Hospitals (HUG).

In India, the Narayana Hrudayalaya Foundation has launched a vast telemedicine project enabling people who live far from medical centres to benefit from a consultation while staying at home.

Cooperation between specialists

Andy Fischer, CEO of Medgate, Switzerland’s biggest telemedicine service, and president of the International Society for Telemedicine and eHealth, believes that closer cooperation between all those involved in treating patients – attending physicians, specialists and hospitals – could make remote consultation more efficient. “When practitioners respond to a patient by phone, they must be able to refer him or her to a colleague or hospital, if necessary,” he says. “The transfer of the digital data collected during the teleconsultation needs to be simple.”

Efficient collaboration also requires harmonising the languages used in e-communications. “Given the sheer volume of data sent and interpreted, a common terminology is needed,” says Alain Junger. “We need to standardise clinical communication.” In addition to 1,000 doctors and 15 clinics, Medgate also integrated a new category of partner into its Medgate Partner network last year: pharmacists. “At 200 different Swiss pharmacies, patients can now receive a remote consultation from one of our doctors,” says Andy Fischer. “The goal is always to simplify access to healthcare as much as possible.”

Access to healthcare for people living in rural areas has improved in recent years thanks to new communications technology. In India, for example, people in rural areas can now receive a drug from the pharmacy by showing the prescription sent as an SMS by their free telemedicine centre. Two thousand people in Mali received a remotely interpreted ultrasound in 2012, and more than a thousand received an electrocardiogram under similar conditions.

The Terres des Hommes Foundation launched a tele-medicine project in Burkina Faso in early 2014 with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “In rural parts of the country, one in eight children doesn’t reach the age of five. That’s mainly due to misdiagnosis, says Thierry Agagliate, who heads the project for the Swiss NGO. Nurses in 400 rural health centres will have access to the latest-generation tablets, allowing them to be connected in real time with doctors at the hospital in their area. In addition, the hospitals will be able to access the electronic files of the patients at the rural health centres and detect epidemiological trends to better understand the difficulties they encounter.”

Fear of losing the human element

Though telemedicine is inspiring much enthusiasm, there is also some cause for concern. One reason is the absence of physical contact. For many patients, the actual presence of a practitioner is crucial to any treatment process. All practitioners know the importance of the body language and mood of a person in consultation. Not even the highest-performance digital tool in the world can convey the feel of a treatment room, the stress of the patient or the sense of what is happening off-camera.

“Telemedicine does not make the doctor-patient relationship obsolete,” says Alain Junger. “It’s not the computer or the screen that are treating the patient. These tools are a reassuring aid in many cases. The sensitivity and intelligence of both caregiver and patient are just as critical today as they always have been. Screen or no screen, it’s still two human beings face to face.”

Thanks to telemedicine, elderly and disabled people are no longer required to leave the house: a practitioner monitors their progress by video conferencing.

At 200 different Swiss pharmacies, patients can now receive a remote consultation from one of our doctors. The goal is always to simplify access to healthcare as much as possible.