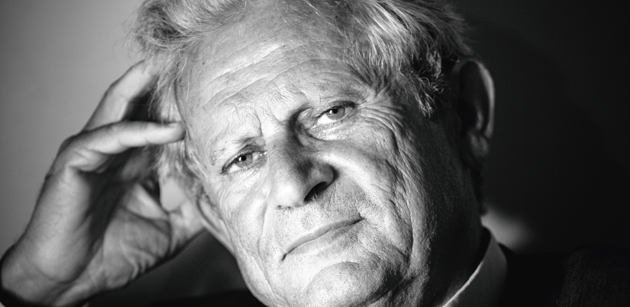

Philippe Jeammet is a Professor Emeritus of child and adolescent psychiatry at Paris Descartes University. Here, he analyses the key role that parents play in their children’s development

in vivo How do you define adolescence?

philippe jeammet It’s society’s response to the physiological phenomenon of puberty. Adoles- cence is not new, but the way we respond to it is new. It’s nothing like the rites of passage in traditional societies that we ourselves had in our childhood, where there was a marker, like in religious tradition, going from the end of primary school to secondary school, standards about going out, what boys or girls were allowed. The structure has totally changed.

iv The notion of freedom comes up a lot in your different books, especially the freedom allowed by parents today. Why is that?

pj I think it’s absolutely fundamental, and maybe even more in the parents’ mind than in the adolescents’ mind. You have to understand that freedom does not mean the absence of rules. Freedom involves other rules, and these rules are expressed differently than they used to be. I believe that we’ve replaced the vertical authority of mid-20th century society, when adults had much more authority. Today, teens can get away with talking to adults in ways that they never would have done before. But that doesn’t reflect a lack of respect. It’s simply that the relationship to hierarchical authority has changed.

Many parents feel overwhelmed and say that if it’s not what they experienced, then it’s not right. But it’s another form of authority that is more horizontal and more taxing for parents. Because they have to defend their decisions. Why are they exercising authority? They can no longer force it on children and say, that’s the way it is and that’s how it has to be done. Adults now have to say, “This is why I don’t agree.” They have to explain themselves, but sometimes parents don’t know what to say. These days, problems arise because the parents themselves are at a loss.

iv What impact does that have on adolescents?

pj If adults are confused, it can lead to anxiety in young people. And nothing is more contagious than anxiety.

iv Many mental illnesses start developing during adolescence. Why?

pj Mental illnesses that often start during adolescence, such as schizophrenia, mood disorders and anorexia, all have something in common. Victims focus inward in response to fear, which is typical during this stage of life.

But adolescence is not an illness. It’s normal! The majority are fine. However, adolescence reveals our own lack of confidence and uncertainty, because during this period, that transformation of the body and of access to adult sexuality drives adolescents to take some distance from their parents and try to understand who they are inside, in their gut, in their minds and draw on their own resources. Through the most fragile individuals, we can see how, over a few years, someone who had an easy childhood – now faced with the task of putting to work what they’ve received from their parents, acting in their own name, enduring a feeling of solitude – can panic and develop powerful fears that will force them, biologically, to react actively to protect themselves and protect their mental balance. When fear dominates, all senses and logic are distorted

iv What does the adolescent risk?

pj All of these psychiatric disorders will lock the individu- al down into one of the three areas that are needed for the personality to develop prop- erly: taking care of their body, developing academic skills and developing sociability. The impaired adolescent will wall themselves in one of these three relationships, sometimes all three. By walling themselves in, they gain control. And that feels safe. “I’m not interested in school. Social life doesn’t interest me. I’m a rebel.” At the time, that protects them because they regain purpose and control. But it cuts them off from worthwhile, healthy relationships. They become prisoners of their own behaviour. The more they’re prison- ers, the harder it is for them to open up to others and the further inward they go. It’s a vicious, pathogenic circle.

iv What role should parents play in the medical care of an adolescent?

pj Sometimes it’s better to leave the parents out of it for a while, not because the parents are bad, but because the relationship is too emotionally charged. For example, with anorexia nervosa, the parent feels relieved when the child eats, but the child still feels anxiety. Or when the child loses weight, the parent stresses, and the child feels guilty. The parents

should stay out of this relationship of tension and

mutual control for a while. Parents need to

understand that this behaviour is not a choice.

They don’t do it to annoy, push or rebel against

them. They do it for a sense of control when they

feel lost. People’s entire understanding of mental

illness needs to change. It’s not a weakness or an

illness in the traditional sense, but an emotional deficiency that makes it difficult to

build mutual relationships with those

around them.

iv What would the best attitude for parents to have with an adolescent who seems lost?

pj For them to say, “Wait, don’t clam up, we should talk about it.” Potentially bring in someone from outside and ask “What do we want, what for, so that we can remain attentive to and considerate of each other’s needs.” Take a step back and figure out how to move forward in this relationship with the child. But they have to talk about it and learn how to use their emotions to avoid building that wall. That’s the message that they should have. Illness occurs when misunderstanding solidifies, but it could develop in a completely different direction. ⁄

Philippe Jeammet is a Professor Emeritus of child and adolescent psychiatry at Paris Descartes University. The French child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst is also president of the organisation École des Parents et des Éducateurs d’Ile-de- France (EPE-IDF), which provides guidance to parents and educators. He has been seeing, advising and listening to adolescent patients since 1968. Philippe Jeammet is the author of several books on adolescents.

«Grandir en temps de crise», Bayard Jeunesse, 2014 «Adolescences»,

La Découverte, 2012 «Anorexie, boulimie: les paradoxes de l’adolescence», Fayard, 2011