By treating the population, the healthcare pollutes enormously. Faced with the scale of the climate crisis, medicine must adjust its practices to become more sustainable.

Pollution makes people sick. But treating them harms the environment and therefore indirectly affects even more people. In Switzerland, healthcare systems generate 6.7% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. That is as much as civil aviation. While that threat, which most people believe is a distant one, intensifies, medical workers have to come to grips with it. “When you’re not confronted with it every day, you can’t entirely grasp the magnitude of the threat,” says Valérie D’Acremont, Head of ‹ Digital and Global Health at Unisanté ›. “The impacts of climate change can be hidden, especially when they accentuate an existing situation.” For example, pollution increases the number of deaths caused by cardiovascular diseases. But the population does not necessarily realise it, because deaths from this disease are common.

“As healthcare providers, we’re in an odd position,” says Renaud Du Pasquier, Chief of the Service of Neurology at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). “We’re a big part of the problem but also suffer some of the consequences, since we’re the ones who have to absorb the increase in patients and treat climate-related illnesses.” This situation is criticised worldwide within the healthcare community. For example, in 2021 more than 200 prestigious health journals, including The Lancet and The British Medical Journal, appealed to the World Health Organization (WHO). Their bid is clear: biodiversity loss and climate change must be considered a single global health emergency.

When listening to medical workers, we understand that the effects of climate change on health are already being felt. “Air pollution is responsible for 3,000 deaths a year,” Valérie D’Acremont says. “That is the number of Covid-related deaths in Switzerland during the four years of the pandemic.” In addition to the physical damage, climate change is also dramatically affecting people’s mental health. “We’ve seen a marked increase in mental breakdowns, people committing suicide, young people suffering from ‘eco-anxiety’, or ‘solastalgia’.” But the healthcare system is not yet ready. “Psychologists and psychiatrists are looking into new ways to support patients.”

These circumstances call on us to urgently rethink the way we practice medicine. Renaud Du Pasquier feels that we cannot wait for future generations to do better. “We need to act now.” As Vice-Dean at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine, the neurologist helped to integrate a sustainability module into the medical curriculum. “There are two key benefits. Young people receive high-quality training so that they’re informed about environmental matters, and teachers are required to keep up to date on issues.”

It is also important to propose concrete ways to change practices. “Now I don’t conclude any talk without a glimmer of hope,” Valérie D’Acremont says. “Otherwise, people are in shock and incapable of doing anything to improve things.” And public involvement is crucial to move closer towards more sustainable medicine. The book Santé et environnement : Vers une nouvelle approche globale¹ (Health and environment – towards a new global approach) brought together a group of experts to identify the key challenges in the relationship between healthcare and the state of nature. To take stock of the current situation and find ways of improving sustainability in healthcare, the issue is considered through the prism of not only medicine, but also philosophy, sociology, earth sciences, biosciences and anthropology.

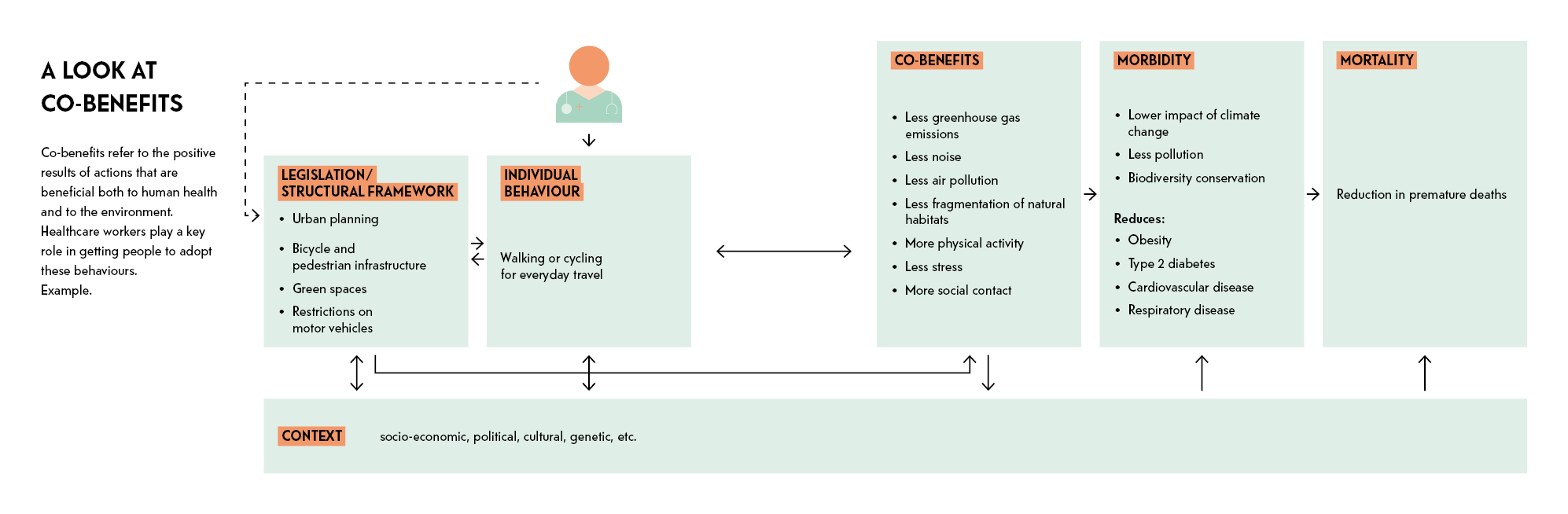

One of the pathways being explored to initiate a change in the way we treat people is to question what makes people ill and then boost prevention measures. Experts looking at solutions to make healthcare more sustainable also agree on the importance of promoting co-benefits. This means inviting individuals to take everyday behaviours – such as in their food choices, how they get around, and their relationship with nature – that benefit both their health and the environment. Citizens should be involved in the process. Good practices implemented in other countries can also serve as examples. “We could take inspiration from the decentralised healthcare system created in southern European countries by developing local community healthcare,” says Valérie D’Acremont. “We could do things differently, design waiting rooms like cafés. We have to open up all possibilities, to develop our strength.”

The quality of life of the most vulnerable declines as temperatures rise. The impact of climate change on mental health is particularly devastating. The latest IPCC report revealed that the adverse impacts of climate change are exacerbated by inequalities related to age, disability and low income. “Newborns, children, the elderly, people with psychiatric disorders, and adults in precarious socio-economic situations are the most vulnerable groups,” says Marc Humbert, Associate Physician with the Service of Geriatrics and Geriatric Rehabilitation at the CHUV.

Extreme heat spikes and heat waves increase cases of dehydration and cardiovascular incidents, while pollution causes respiratory problems. “The elderly are at risk of heat stroke, for example. Environmental factors such as social isolation, lack of air conditioning and substandard housing can also amplify vulnerability,” Marc Humbert explains.

In the book Santé et environnement, the experts agree that the effects of climate change on mental health remain underestimated. “For example, natural disasters are 40 times more likely to impact mental health than physical health. The gradual shift in temperatures can also negatively affect mental health. A 1°C rise in the average temperature in a region induces a 2% increase in the prevalence of mental health issues, or 160,000 new cases in Switzerland. These factors will be a heavy burden on healthcare costs,” says Philippe Conus, chief of the Service of General Psychiatry at the CHUV.

If exposed to a climate event, some individuals end up in situations of psychological distress, to the point where the outcome can be fatal. “People whose livelihoods depend on nature are affected most. In some countries, the suicide rate among farmers doubled during periods of drought,” Philippe Conus says. It has also been found that direct experience with a natural disaster can have consequences on mental health, such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Furthermore, the condition of mental health patients can worsen after a climate event. “Someone with bipolar disorder whose circadian rhythm is disrupted because of the heat will be more likely to go into manic episodes,” Philippe Conus says. A study published in the American journal Science also showed that a person with schizophrenia were three times more likely to die during a heat wave than the rest of the population.

Eco-anxiety is described as the psychological effects caused by awareness of the threat of climate change. Defined in Santé et environnement as a “feeling of anxiety exacerbated by a feeling of powerlessness”, eco-anxiety is nevertheless perceived as a healthy reaction to a situation that is considered very real by health professionals. “Eco-anxiety points to a collective problem, in that we need to rethink our social, economic and lifestyle models,” says Sarah Koller, ecopsychology researcher and practitioner at the University of Lausanne. “The pathology, however, is denial,” Philippe Conus says.

A survey conducted by University of Bath researchers in 2021 reported that three-quarters of people aged 16 to 25 found the future frightening. “The idea of emerging from a growth economy can seem like a total collapse. But eco-anxiety subsides when used to promote a transition to alternative systems, and when it leads us to think about ways of living, travelling and working in a greater respect for living things,” Sarah Koller says. “What’s important is to shake ourselves out of it and develop the motivational forces that drives positive action.”

Restricting the excessive use of treatments in hospitals is one of the goals pursued by Marie Méan, Senior Physician at the CHUV and lecturer with the Faculty of Biology and Medicine at the UNIL, in her research and day-to-day practice. “To avoid unnecessary treatments, we must prescribe rationally, according to the usual recommended doses and review patients’ medications regularly, even if that means deprescribing some, with the approval of the patients and their attending physician.”

Prescribing for an appropriate and limited amount of time is also important. “Take the example of antibiotics given to fight an infection. You have to aim for the shortest duration possible and make sure that the patient complies with the prescribed duration,” she says. Research shows that limiting the duration of antibiotic treatments reduces side effects, resistance and drug pollution of the environment. “In the case of pneumonia, which is a frequent reason for hospitalisation, a five-day course of antibiotics is most often effective. Sometimes even three days is enough.”

On discharge, people hospitalised for an acute problem receive a complete pack of the prescribed treatment rather than the exact number of tablets needed. “Some medicines end up in waste collection centres, pharmacies or, even worse, flushed down the toilet. This waste is avoidable, which is even more important when certain medicines are in short supply.”

A prescription can therefore be avoided, shortened or cancelled, and also replaced, Marie Méan says. A chronic treatment can sometimes be avoided with changes to lifestyle, e.g. more exercise or a healthier diet that includes less animal protein and sugar. “Stimulating patients to get out of their hospital bed several times a day helps to prevent thrombosis, thus eliminating the need for pharmacological treatment. Mobility also produces a wide variety of positive effects, including reduced depression and improved sleep, and patients return home faster. Herbal treatments might also be an option. “That’s actually what we use for hospital patients with insomnia. But to prescribe more sustainably, the pharmaceutical industry would have to publish data on the ecological impact of drugs, from research and manufacture to distribution and marketing.”

As a major polluter, the healthcare system is not environmentally or financially sustainable in the long term. How can hospitals review their operations to improve their sustainability? “The goal is to transform hospitals to make them more sustainable,” says Nicolas Senn, chief physician with the Department of Family Medicine at Unisanté and Professor of Family Medicine at UNIL. To make their practices more eco-friendly, hospitals can start by assessing their carbon footprint to identify the sources of emissions and where they can be reduced or eliminated.

Hospital buildings use a lot of energy. Eco-design and green lab design approaches should be promoted to reduce their carbon footprint. These help to minimise the use of energy, water and materials, while improving the efficiency of processes. Meanwhile, eco-design mainly focuses on optimising and reducing heating and insulating buildings.

Day to day, hospital staff should sort and reduce waste. Reducing unnecessary medical procedures is another important strategy. Namely, scanners and MRIs, which are major sources of air pollution, and are over-prescribed. “An estimated 20% to 40% of exams are of no benefit to patients.” A “green” approach should be taken with surgery as well, choosing as much non-disposable material as possible, from certified sources and that can be reused, while administering anaesthetic gases that are least harmful to the environment.

Encouraging the rollout of procedures that have co-benefits is also key. A considerable amount of hospitals’ CO2 emissions come from the transport of patients and staff. “Promoting non-motorised mobility generates co-benefits, for both patients’ health and the environment. The same goes for food. A diet with fewer animal-based products benefits both people and the planet.”

At present, Switzerland’s healthcare systems mainly focus on curative services based on a biomedical model. For more sustainable medicine, these systems need to shift towards a preventive approach, as recommended in the roadmap presented by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences.² Finally, healthcare allocation can also be rationalised through telemedicine, e-health and by merging hospitals to improve the coordination of services.

“In the 2000s, when I was working as a tropical medicine specialist in Africa, I noticed how quickly climate phenomena could evolve,” says Valérie D’Acremont. “I became aware that I was witnessing what awaited us in the future, in Europe. Basically, decreasing agricultural yields, desertification, and, as a result, food problems.” Although, for the time being, access to food is still guaranteed in most European regions, other problems are arising.

Due to climate disruptions, exotic insects can survive in Switzerland and sometimes transmit tropical diseases. “The problem is that for now when you’re bitten by a mosquito, you can’t imagine that it could be a problem. And when doctors see people with a fever, their first thought is that it’s the flu, whereas it could actually be a new disease that has just arrived in Switzerland.”

Another major consequence of the changing climate is the migration of people, forced to leave regions that are becoming unlivable. However, climate refugees currently have no officially recognised status and therefore no access to healthcare. This issue is of particular concern to Patrick Bodenmann, chief of the Department of Vulnerabilities and Social Medicine at Unisanté. He is working to extend care to meet the needs of marginalised people who have been forced into migration due to climate change. “Health equity, applied to medicine, does not aim for the same care for everyone. Instead, care is adapted to the specific needs of each patient by integrating the socio-economic determinants of health their vulnerabilities and their potential for resilience.” In addition to unequal access to healthcare, the impacts of climate change are bringing a major global imbalance. The poorest countries have to bear far more of the health burden due to the climate crisis, even though their contribution to the problem is significantly less.

The major factors that are aggravating the situation and where action is needed as quickly as possible are deforestation, intensive livestock farming and uncontrolled air travel, Valérie D’Acremont says. “For the healthcare system, we need to stop the hospital-centred approach and reinforce prevention and community care. Hospitals have everything to gain from it.”

With the goal of transitioning towards a more sustainable world, health can play a key role in increasing people’s concern about climate change,” writes Anneliese Depoux, a specialist in media coverage of health crises, in her contribution to the book Santé et environnement. This view is shared by François Gemenne, Director of the Hugo Observatory³ in Belgium, who wrote the preface to the book. “Health, because it touches the most intimate part of us, our primary interest, it can also be a powerful lever for action to protect the environment.” Healthcare systems that generate a significant amount of pollution by treating people who are often ill because of the current state of the environment also play a major role in shaping people’s behaviour. Finally, this situation confirms that it is impossible to think of environmental and health emergencies as two distinct things if we are to create a more sustainable future. /

Number of people who die of air pollution per year, in Switzerland

/

Proportion of 16 to 25 year olds who think the future is frightening.

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a magnetic field of between 1.5 T and 7 T (tesla, the unit of measurement for magnetic flux density), while recent low-field MRI scanners have a range from 0.1 T to 0.55 T, says Alban Denys, chief of the Department of Radiodiagnostics and Radiology at the CHUV. “Low-field MRI requires less helium, a rare and limited gas on Earth, consumes less electricity, is lighter and requires less space to install.”

With global warming, this invasive species is now in Switzerland. Control measures have been taken to limit the spread of these potential disease-carrying insects.

• Remove any uncovered containers of water from your terrace or balcony.

• See your doctor if you have fever symptoms after returning from a trip.

• Report any active mosquitoes on the national website moustiques-suisses.ch

Protect yourself

- reduce physical activity when temperatures are highest

- prefer shaded areas

Avoid the heat – keep cool

- close windows and blinds during the day

- air out at night

- wear lightweight clothing

- stay cool by taking

cold showers

- place cold cloths

on the forehead, back of the neck, hands and feet

Stay hydrated – eat light

- drink at least 1.5 litres of fluids per day and don’t wait until you’re thirsty

- eat cold, refreshing meals

- make sure your salt intake is adequate

Source: Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), “The three golden rules

in a heat wave”.

Heat stroke symptoms to lookfor in an elderly individual: