An In Vivo team was given behind-the-scenes access to a promising clinical trial conducted in Lausanne, which tackles melanoma by focusing on adoptive cell therapy. From obtaining consent to reviewing the results, the team shadowed the first patients to be included in this unique research protocol in Switzerland.

It is in a rather sober consultation cubicle on the 6th floor of the main building of Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) that the patients shortlisted to participate in the clinical trial called “ATATIL” discover what awaits them. The title of the consent form alone takes up three lines: “Phase I study to assess the feasibility and safety of an adoptive transfer of autologous tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in conjunction with IL-2 administration, followed by nivolumab maintenance in patients suffering from advanced metastatic melanoma”. This is followed by 27 pages that set out the details of an exceptionally complex process that required a year’s preparation and specialised training for 65 hospital professionals, led by Prof George Coukos, director of the UNIL CHUV Oncology Department, and by Prof Lana Kandalaft, director of the Centre for Experimental Therapies.

From the first appointment, Dr Angela Orcurto, clinical director in the Immuno-Oncology Unit, gets straight to the point so that patients really understand “the nature, importance and scope of the study”. She explains stages and side effects, active substances with barbaric names, risks and benefits, not to mention that there is no guarantee of success. Even if the cancer has resisted previous treatments, “patients need to know if there are other options available to them, and that they can revoke their consent and withdraw from the trial at any time, without giving a reason,” she emphasises. When the interview is over, they will have a “reasonable period of time to consider the matter” at home, with their loved ones, before making a decision.

“If there’s one thing I’ve understood, it’s that this treatment is not like the others!” exclaims Robert*, one of the very first patients to have given his consent.

“I didn’t hesitate to say yes for a second, as the principle seems to me to be very logical: your cells are removed, they’re boosted and re-injected,” confides Pierre*, who is accompanied by his son-in-law. “It’s not that I don’t understand it myself, but I’m counting on him to explain it all to the family,” he says. “It would be too much for me otherwise.”

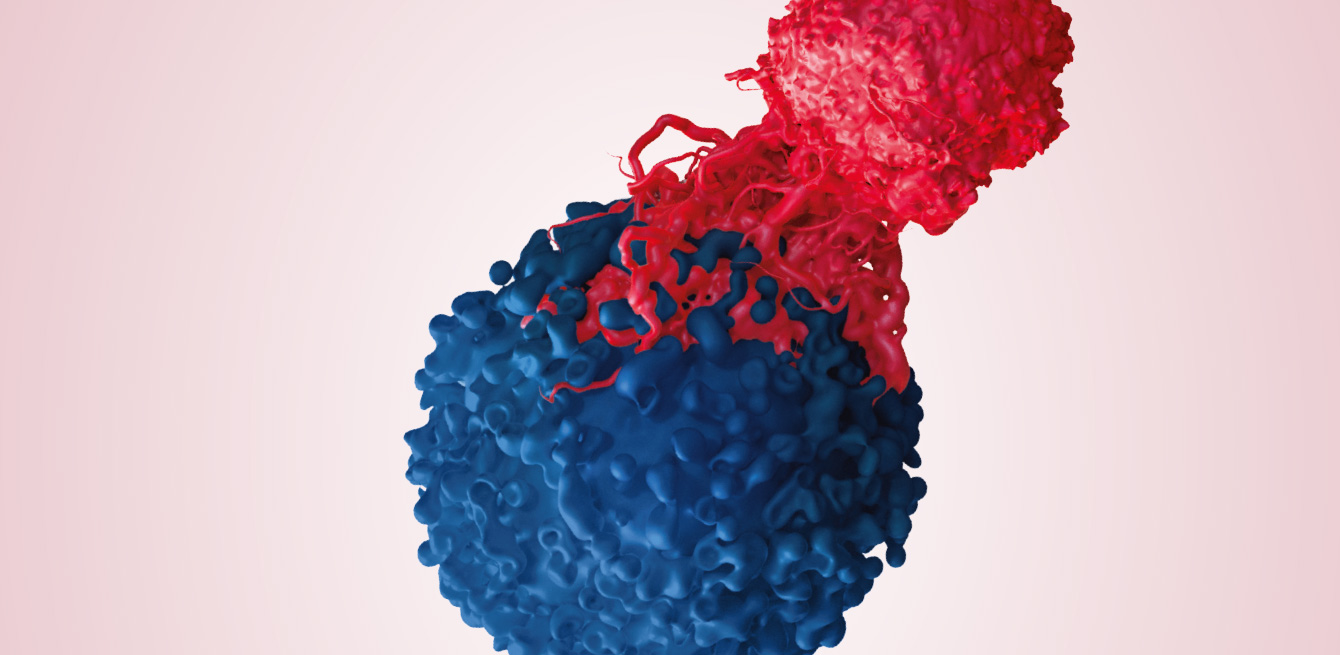

The mainstay of this trial – adoptive cell therapy – involves removing Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) from the patient, proliferating them in the laboratory, then infusing them into the same patient after preparing the ground with chemotherapy. As these cells come from the tumour itself, they will recognise, attack and destroy it once they have been re-injected into the body. A trailblazer in this field, the team led by Dr Steven A. Rosenberg, from the National Cancer Institute in the United States, showed a regression of the cancer in around 50% of patients who had received an infusion of T lymphocytes, and complete regression of the tumour during the following five years in 15% of these patients.

As the first centre in Switzerland to offer this type of personalised immunotherapy, CHUV relies on a certified laboratory that ensures the cells are handled and modified under strict safety conditions, and by a trained team of doctors and nurses, capable of managing the side effects, among other things. One of the side effects most feared by patients is hair-loss, caused by the chemotherapy that precedes the infusion of the TILs. However, the list is six pages long and “there can be reactions to the treatment that no one has ever considered,” Dr Orcurto emphasises. This is, moreover, the main challenge of phase I: observing the effects of the treatment in ten or so participants before it is possible to consider a phase II, or “pilot study”, extended to a hundred or so volunteers.

“We don’t move to the next phase unless the expected benefit for the patients is greater than the risk,” comments Prof Kandalaft.

“The list of all the side effects is frightening, but I’ve decided to listen to the experts, whom I trust,” confides Robert. Pierre takes a slightly different approach: “Of course, the thought that I’m going to have side effects of varying levels of severity worries me. I know, for example, that I’m going to lose my hair, but I’ve brought a cap with me and I’d like to think that it will be OK.” Without doubt, the two men are “tough”, and this personality trait is also important, according to Prof Coukos, lead investigator of the study.

Pierre and Robert are amongst some 2,700 people who are diagnosed with melanoma each year in Switzerland. The Swiss Confederation is, moreover, one of the countries in Europe that is most affected by this form of skin cancer: one person in 50 has a risk of developing it over their lifetime. Pierre discovered his disease in 2001, and Robert in 2015.

“I was working bare-chested on a building site at Bern Hospital, when a doctor happened to notice a mole on my back and advised me to go for a check-up,” says Robert, a building contractor. “The diagnosis? Stage 5 melanoma: it was a slap in the face.”

As for Pierre, a prison manager, it was when he got home from work one day, on the eve of his 50th birthday, that he felt a lump while taking a shower. Initially inconspicuous, the melanoma grew slowly, then spread.

When the tumour has extended to other parts of the body, as with Pierre and Robert, immunotherapy is poised to become the first-line treatment. “Melanoma is one of the most mutated of all cancers and readily metastasises. However, the greater the damage to the cells, the more visible they are to the immune system,” explains Prof Olivier Michielin, director of the Analytical Personalised Oncology Division at CHUV. The principle is to attack the tumour not with chemical molecules, but by stimulating the patient’s immune system, which will attack the tumour itself. “It’s now possible to stabilise nearly 40% of patients in the long term — unprecedented for this type of disease,” Prof Michielin points out. However, there is still a very real risk of side effects with potentially fatal consequences, in particular autoimmune reactions.

“With the TILs, we are aiming to add another string to our bow and expand the arsenal of immunotherapies,” he adds.

“The adoptive transfer programme focuses on tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes, which appear to be less inclined to attack other healthy organs.”

Pierre firmly believes in this experimental treatment. It was his doctor at the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) who suggested that he participate in the trial conducted at CHUV, while he was mentally preparing himself to start palliative care. He decided to get a dog to keep up his spirits: “I went to Bordeaux with my daughter and son-in-law to pick him up. He’s a five-year-old show dog, a miniature schnauzer. I wasn’t able to get a puppy because I wouldn’t have been able to train him.”

From the moment they sign the consent form, patients undergo a number of tests to determine whether they are suitable for the treatment. “They need to see whether your heart will keep going, your lungs, the platelets in your blood,” explains Pierre. “At each stage, the professionals give you the results of the previous examination, and if they’re good, you get an appointment for the next one. But the fear that they’ll say no to you is always there.” Ultimately, it is the cells that run the show.

“The first thing we do, even before they sign the consent form, is to schedule a biopsy,” explains Virginie Zimmer, a clinical research assistant in the UNIL CHUV Oncology Department, who coordinates all the appointments and ensures strict adherence to the protocol. “This sample is used as the basis for determining whether there is a sufficient number of tumour-infiltrating T lymphocytes to ensure that the initial phase of expansion in the laboratory will be satisfactory. If this is the case, we will then schedule the resection surgery.”

In order to be able to grow the culture, “Prof Coukos and his team need at least 3 cm3 of tissue,” explains Prof Nicolas Demartines, head of the Visceral Surgery Unit.

“The removal of the specimen is a race against time as it’s only possible to cultivate living lymphocytes,” he states. We have 20 to 30 minutes maximum between the surgery and getting them to the laboratory.”

For all the professionals involved, from 13 different fields, the challenge is to ensure that the big day of the infusion in the hospital coincides with the day on which the cells are harvested in the laboratory: “We have a well-established chain of communication so that we can get organised as necessary,” explains Zimmer. However, as is the case with every new protocol, there are many unknown risk factors. “It took five days for my lymphocytes to start multiplying: it was a long time,” confides Angelo*, 44, the third patient we met during the trial. Living in the eastern Swiss canton of Graubünden, he had to travel across Switzerland to undergo the experimental treatment at CHUV. “There are mixed expectations,” comments Philippe Gannon, who is in charge of cell production. “For one of the patients, we harvested 600 million lymphocytes in 13 days, and for another, 80 million in 35 days.” Is there a risk of failing at this stage? “A technical problem can occur, despite everything we do to minimise such occurrences,” confides Zimmer. “Alternatively, everything might be going well technically speaking, but the cells may not be multiplying sufficiently to allow the infusion.”

Provided a major hitch does not disrupt the sequence, exactly seven days before the infusion, the patients are hospitalised for a three-week period. From then on, they will be monitored in the mornings and evenings by the same medical and nursing team. The nurses and doctors will generate 536 notes on average for each patient. These notes will then be transcribed into the study’s database by the data managers, like Amélie Roten: “I record all the medical data required by the protocol, relating to the physical examinations, the blood tests, the side effects, the medications taken and the tumour assessments. This subsequently makes it possible to conduct statistical analyses and establish the safety and efficacy of a treatment.”

The period of hospitalisation begins with so-called “lymphodepleting” chemotherapy lasting five days, with two days of rest. The aim? To prepare the body for the infusion of TILs by shutting off the immune responses. It was a terrible shock for Pierre: “I’d never had chemo before. So, within 3-4 days I ended up with no white blood cells and no hair. But all the same I didn’t look too bad,” he now says, smiling. “The nurses told me that I looked like an American actor.” During the chemotherapy, Pierre sleeps a lot and does not want his family to visit him: “It’s a personal choice”, he simply says.

The big day of the infusion finally arrives. “Although you’re worried, this is the moment you’ve been waiting for,” confides Pierre. The 300 ml transfusion bag, filled with a whitish liquid containing between 50 and 75 billion lymphocytes, is transported carefully from the laboratory to the hospital. At the same time, the patient is transferred to an isolation room. Inside, six professionals take control, but several others observe what is happening from behind a glass pane.

When the carrier arrives with the bag, Dr Lionel Trueb, an associate physician in the Immuno-Oncology Unit, meets him at the entrance to the room and immediately checks each data item. He specifically notes the arrival time and temperature of the bag. “It’s all yours now,” says the carrier who gently hands the bag to the doctor, who then enters the room, where everyone is holding their breath. The contents of the bag can be used for only a hour: after that they will be deemed to have expired. There won’t be a second chance – it’s “now or never”.

Once the bag is in place, the liquid begins to trickle, drop by drop. Each millilitre contains 183 million cells. For Pierre, it’s time to say “Welcome home!” to his lymphocytes. Thirty minutes later, the first effects are felt:

“You suddenly feel it in your legs and you start shaking uncontrollably – it’s like being in a trance, very draining,” Pierre says.

The adoptive transfer of TILs can, in fact, cause symptoms similar to those observed during blood transfusions: fever, shivering, dyspnoea, rashes, nausea and headaches. They usually recede quickly.

The following two weeks are decisive for the treatment’s success. After the cells have been infused, the patients are administered very high doses of interleukin-2 (IL-2) every eight hours. The purpose of this product is to “boost” the anti-tumour activity of the T lymphocytes. However, the body may react to this extreme stimulation, in the same way as during septic shock.

“It’s dreadful,” Robert says. “I wanted to be strong, not to shake, but you can’t help yourself. I wanted to stop after the 5th dose.”

His wife adds: “He was all red, like a tomato”. Robert will ultimately receive six doses of interleukin-2, out of a maximum of eight planned.

When the effects of IL-2 have worn off, the patients can start on the road to recovery, whilst still under close observation. If everything goes to plan, they will return home at the end of three weeks. They will then have three check-ups at 14, 21 and 30 days, followed by visits every three months, in addition to being required to undergo regular imaging exams for five years to monitor their situation. In some circumstances, a maintenance treatment with nivolumab, a tried-and-tested medicine for melanoma, may also be initiated for a maximum of two years. Here too, the aim is to stimulate the T lymphocytes so that they continue to actively destroy the tumour.

After his experience at CHUV, Robert decided to return to work immediately: “Having my own business helped me. In the beginning I was working at 50% of my capacity, I was standing up between two and three hours a day and I was mostly checking other people’s work, but I’m now working at 100% and work is the only thing I enjoy.” Despite a case of vitiligo, which flared up after the treatment and which he found “rather revolting”, the results of his medical examinations are encouraging and the cancerous lesions have receded.

For Pierre, it was when he left the hospital that things became complicated. He found he was suffering from pain in his shoulder blades. He returned home only to find that the pain was getting worse and morphine no longer helped: “From one day to the next, I could no longer walk.” He was beset by uncertainty. So he went back to CHUV, where he discovered he was suffering from a neuromuscular autoimmune disease known as Guillain-Barré syndrome. It starts in the legs, where the immune system attacks the peripheral nerves, causing paralysis. As a result of this unexpected side effect, Pierre will have to stay in hospital for almost three more months and for two months in a rehabilitation clinic very close to his home.

However, this misfortune, which he now refers to as a “small test to pass”, does not detract from his results. Nine months after agreeing to take part in the ATATIL clinical trial, 85% of his metastases have disappeared

“I’ve never had dark thoughts or regretted participating in the trial,” Pierre says. “In 2017, I was told that I had only a few months to live. So I’m not doing too badly.”

Pierre maintains that he has always been a fighter and emphasises that the doctors and nurses must have realised it: “I’ve only ever had dealings with people who wanted to fight alongside me. Occasionally, I wondered if I would get through it, but things are gradually falling into place and I’m on top of it now.” A point of view that is not so far removed from that of Zimmer, who is still following the trial, phase I of which is coming to an end, with her colleagues from the Centre for Experimental Therapies: “For the first patient, it was a steep learning curve – three weeks in hospital, the new interactions with the doctors and nurses, the amount of data generated and the side effects. But we’re learning every day and we’ve put the tools in place to monitor this type of study under optimal conditions.”

Like Robert, Angelo, and the other seven patients who were the first to be admitted to this unique research protocol in Switzerland, Pierre is hopeful that it will offer a road to recovery for as many patients as possible. “I’ve had the good fortune to benefit from this possibility,” he points out, “and I’m also doing it for others.” Does he remember a particular moment in his odyssey as a “pilot patient”? “It was the middle of summer, it was very hot and I was eating ice cream in my room with the doctors and nurses. It was just being alive…”

*Names known to the editorial team

Deaths linked to melanoma each year in Switzerland, according to the National Institute for Cancer Epidemiology and Registration (NICER).

The “weight” of the research protocol for the ATATIL clinical trial, which targets metastatic melanoma.

Ongoing immunotherapy clinical trials throughout the world, according to a count by the American Cancer Society in July 2018.

The protocol is explained in detail to the patient, who must provide formal approval. Hopes, risks, side effects: no question is avoided.

To determine whether cell therapy has any chances of succeeding, a part of the melanoma is surgically removed and sent to the laboratory for analysis.

The patient undergoes a series of tests to confirm whether all conditions are met to participate in the trial.

In the laboratory, the lymphocytes in the tumour, called T lymphocytes, are isolated. They have 14 days to multiply by the billions.

The patient undergoes chemotherapy for a week to reset immune defences and prepare for the reinjection of the T lymphocytes.

This crucial, delicate step is when the patient is reinjected with his or her own cells under close medical supervision. The cells must go head to head with the metastatic melanoma.

Once reinjected into the patient’s body, the T lymphocytes continue to be boosted through infusions.

The body and mind recuperate, still under medical supervision. If feeling good enough, the patient can go home.

Did the T lymphocytes do their job? Thirty days following reinjection, the patient has a scan to deliver the initial results of this first offensive.