There have never been so many people in the world over 100. The emergence of the fourth age in rich countries has rekindled old dreams of immortality, pushing medicine to develop new practices.

Was Jeanne Calment, who holds the record for the world’s longest lifespan after officially living to the ripe age of 122, a fake? The doctors who validated the French supercentenarian’s age are going head on with a team of Russian researchers who claim that her daughter, Yvonne, who died in 1934 according to government registers, stole her mother’s identity to avoid paying inheritance tax. If her age proved to be a hoax, the American Sarah Knauss, who died in 1999 at 119 years old, would be posthumously given the title of the world’s oldest person ever. The oldest person alive today is Kana Tanaka, who celebrated her 116th birthday on March 9, 2019, in Fukuoka, Japan.

Supercentenarians—or people older than 110—remain statistically rare, but the growing phenomenon has highlighted the issue of longevity. Lifespans continue to lengthen in "developed" countries, bringing about a new stage in life dubbed the "fourth age". Four generations can now be alive at the same time. The proportion of "old-old people", i.e. over age 90, has never been so high in industrialised countries. According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, the number of centenarians almost doubled between 2000 and 2017, rising from 784 to 1,510 (0.18% of the population). Experts forecast that nearly one out of five boys and one out of four girls born in 2017 will live to see 100. Some experts, such as the French geneticist Jean-Louis Serre, believe that human lifespan has a definite limit, and that maximum life expectancy has already been reached. Meanwhile, others, including Italian researchers Elisabetta Barbi and Francesco Lagona, posited in the journal Science in 2018 that risk of death levelled off after age 105, suggesting evidence of what they call a "mortality plateau".

Humans have always fantasised about eternal life, from the Fountain of Youth in the Garden of Eden, which supposedly held the power of regeneration, to scientific research into transhumanism. Using medicine, hormones, cryonics (the process of deep-freezing living organisms) and even "downloading our consciousness", supporters of the movement are working to improve the human condition, possibly to the point of making us immortal.

The famed British biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey believes that to avoid death, we need to eradicate the causes. Google has gotten in on the game by investing in the development of nanobots that swim through our bodies to fight disease. These schemes disrupt our traditional concepts about life, as life is structured by the certainty of death.

"Death is part of our existence in this world, part of the human condition. Getting rid of death means giving up our humanity," says the French philosopher Franck Damour, a critic of transhumanism.

By adhering to the traditional philosophical perspective, he believes that being human "means knowing that death is the inevitable outcome, while at the same time, refusing it. This contradiction is the very essence of human life!"

His colleague Jean-Michel Besnier discusses the paradox of wanting immortality, which eliminates the symbolic element that gives a human meaning to our existence as mortals: "Progress in biotechnology suggest that our biological processes could continue functioning without deteriorating. The living being in us would survive, but what about the human being? The techno-prophecies of transhumanism scoff at the human adventure that gives meaning and appeal to culture. What would literature or music be without death? We don’t love life if we think of it in terms of algorithms."

Read his interview (in French)

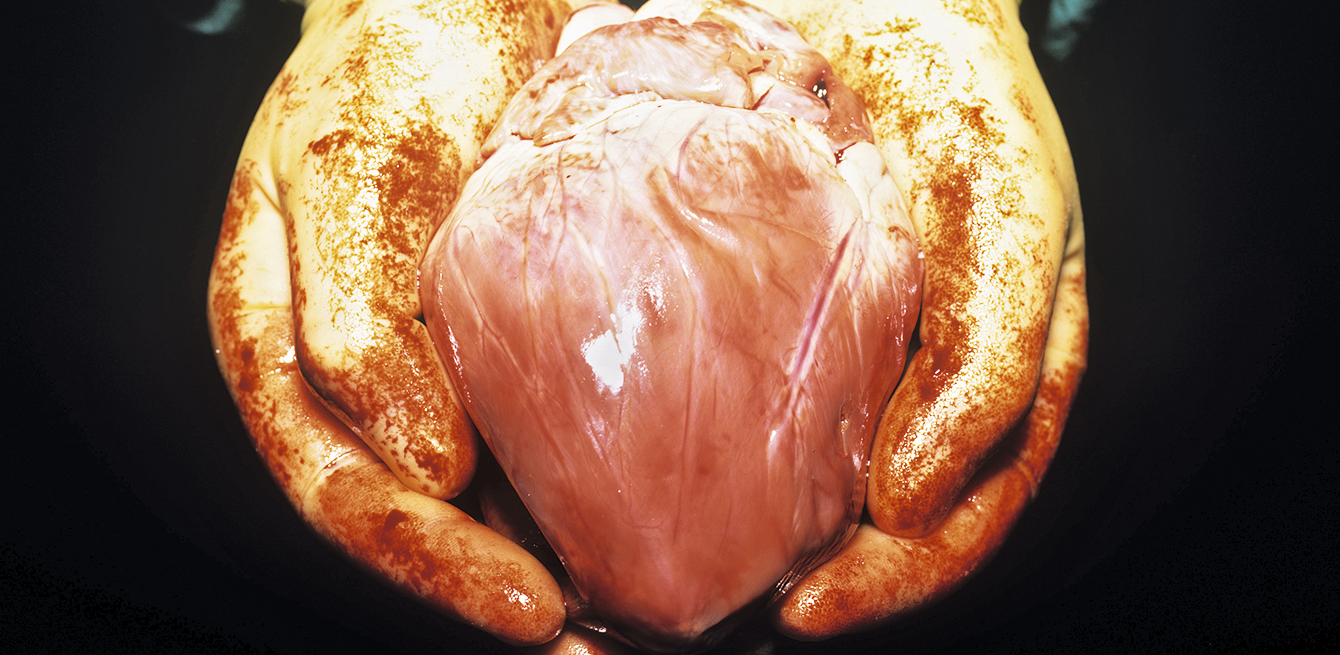

At a more modest level still far from the utopia of immortality, technology has already improved the quality of life and medical care for elderly patients. For example, doctors at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) can now replace heart valves without opening the chest. The technique, called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), offers the immense advantage of avoiding open-heart surgery, which carries such a high risk for older patients. Using this method, a new valve is inserted through a tiny opening—most often through the femoral artery in the thigh, but if obstructed, it can be done through the neck—to push out the damaged aortic valve.

"It is often used on patients aged 75 and over, whose health is more fragile and who often suffer from more than one serious condition. That makes them more vulnerable," says Stéphane Fournier, Chief Resident of the Cardiology Service at CHUV.

"Recovery is also shorter with this procedure than with traditional surgery." Other hospitals are perfecting "mini-invasive" techniques that are more appropriate adapted for older patients, such as uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), available for example in Bern and Ticino. VATS is used to perform pulmonary resections in treating lung tumours with a single incision, just a few millimetres long.

Until the 1970s, life expectancy rose due to the decrease in premature deaths. These days, it continues to climb as the mortality rate drops in people over 65 thanks to scientific advances. The extensive research led by James Vaupel, an American expert in demography and ageing, suggests that 75 is the new 65.

Today, people aged 75 are as healthy as 65-year olds were 50 years ago.

"In Switzerland, medical care contributes to a life expectancy of 81 years for men and 85 for women," says Professor Christophe Büla, chief of the CHUV Geriatrics and Geriatric Rehabilitation Service. The darker side of the increase in life expectancy is that people can develop multiple chronic conditions at an advanced age: heart, failure, kidney failure, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, etc. He added that women live longer but experience more illness.

Most areas of specialised medicine are now struggling with the growing population of elderly patients. "They were developed for younger patients, with one condition. But suddenly, we’re dealing with patients who have three or four at the same time," Dr Büla says.

Awareness and adjustment to this situation vary, even if new sub-specialities are emerging, such as orthogeriatrics, oncogeriatrics, etc. Another issue is that few clinical trials include elderly subjects with several pathologies. Furthermore, even if some procedures are technically feasible, such as tube feeding in patients with dementia, the medical staff has to grapple with the ethical questions that arise, says the geriatrics specialist from CHUV.

"We can extend a person’s life, but what will the quality of that life be? Is it worth it treating someone who is 94 using chemotherapy, with all its side effects, so that the person can live another six months? Or is it better to invest in their quality of life?"

Professionals are divided on these sensitive issues related to excessive treatment. On one side are those who want to use every possible option to help patients live longer, even if the person is very old, while on the other are those who believe that it becomes excessive after a certain age, and that some treatments should not be considered.

Shouldn’t it be the patient who makes the final decision? Focus has shifted to ways of better respecting the independence of elderly patients and their wishes when it comes to their health and the end of their life.

Read the interview (in French)

"The elderly have very different preferences and levels of health. People of the same age with the same disorders can have different wishes. Some want to continue living no matter what, while others have had enough. Some even want assisted suicide, but that remains a minority." People grow increasingly dependent in the months before death. Through a set of actions encouraged by geriatric medicine, such as physical activity, good nutrition and social involvement, dependency can be reduced. Dependency doesn’t have to be inevitable.

"A recent study in Denmark of people currently over 100 showed that they are not only in better physical and mental health than 20 years ago, but nearly half are independent in everyday life. That upends our preconceived notion of the very elderly person who loses all independence," Dr Büla says.

Hospitals are also trying to adapt to ever older patients. Cédric Mabire, a researcher in nursing at the University of Lausanne, developed a project on the values of healthcare providers in dealing with the very old. "We surveyed 80 healthcare staff members from different services with a high proportion of old patients. The idea was to share common values to improve our care practices." This analysis shows the importance putting people first in adapting the hospital environment and ethics of medical care (instead focusing on the illness). "Hospitals are built to treat acute disease," Mabire laments. "The system is not designed for caring for chronic diseases, which are increasingly common, and their structure and organisation are not adapted to older people."

He gives the example of informational signs, suggesting that there should be more of them and that they should be written in larger characters to help senior citizens find their way. And easier access should be provided for people with reduced mobility, especially avoiding stairs to reach a lift. He also indicates that staff should speak louder, more slowly, and take the time to explain things. The pace of procedures at the hospital is another problem, for both healthcare staff and patients.

"Everything happens too quickly – meals, washing, medication. Everyone realises that the pressure of the speed with which things are done at the hospital is not adapted to the needs of the elderly."

Simple acts can reflect respect for the independence of older patients. "For example, instead of putting pills in their mouth, we can leave patients the pillbox, let them check it, and take it themselves. In one week, if people are excessively treated like a child or told what to do, they can lose the physical and mental ability to take it on their own," Mabire says.

Contrary to what many people think, most people aged 90 and over live at home, says Alain Huber, secretary of Pro Senectute in French-speaking Switzerland. "Old-old people want to be assisted and cared for at home and, if possible, to die at home. To keep them there as long as possible, we have to work as a network, with relatives, loved ones, neighbours and social organisations." In any case, long-term care facilities are already at full capacity. Any availability in the future will depend on the town or canton.

"New, alternative forms of accommodation are available,” Mr Huber says, “such as situations where students stay with the elderly and do some cleaning, or day centres for people with dementia, to relieve their loved ones."

Pro Senectute supports the rights of senior citizens in different ways. The organisation works to fight ageism, or age-based discrimination, and is planning a symposium on the subject in November 2019. "One of many examples is the additional costs charged to older people to make their payments if they don’t have internet access." Studies, such as the research led at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Bern, have pointed to a worrying increase in senior poverty. In 2015, 12% of senior citizens received Switzerland’s supplementary benefits, up from 5.9% in 1999. "We often have people who need glasses because they’ve lost or broken theirs and can’t afford to replace them," Mr Huber says.

For the visually or hearing impaired, not having the right glasses or hearing device can have adverse psychological and social consequences. "People wait an average of seven years before seeing a doctor about their hearing and getting a device. It’s too long," says Mr Huber. Health issues are often the root cause of loneliness, another significant challenge facing those over age 75 to 80.

"Hearing loss makes it hard to go for coffee with friends. Reduced mobility is another isolating factor. They can’t go out if it’s raining or snowing. Or if they are visually impaired or have problems with balance. They feel more vulnerable and stay at home."

Unless they have younger people around them, this social isolation is made even worse, as they lose more and more friends their age after age 85. But they can stay in good physical condition for a long time. "Just a few simple, regular muscular exercises can help," Mr Huber says.

On top of the social and health challenges raised by increasing longevity is the inevitable issue of financing the national health system. Especially with the gap between the number of people in the working population and all the baby boomers about to retire. People aged 65 and older currently represent nearly 18% of the Swiss population. In 2050, that percentage will be 27%. That means that spending related to the dependency of the elderly will sky-rocket.

In Switzerland, spending on dependency currently stands at 1.5% of GDP. “Forecasts estimate that will double by 2030,” says Christophe Courbage, professor at the Haute École de Gestion in Geneva.

Home care currently costs 1,200 million Swiss francs every year, while the cost of facility care is close to 8,000 million Swiss francs. "If we don’t do something about it quickly, we’re headed for disaster," the economist warns. Dependency costs paid by families are likely to rise significantly, and Switzerland is already the country where these costs are highest. "Their loved ones could be driven into poverty," Mr Courbage says.

Dependency costs for the elderly are currently financed by national health insurance systems. New ways of paying for it are being debated. "One of them is "inheritance collection", or deducting dependency benefits from the future inheritance, under certain conditions." Certain cantons in German-speaking Switzerland have already implemented a point-earning system for informal care. "Anyone offering care earns points, which they can in turn exchange for care if they need it," Mr Courbage says. Another idea is to create a public dependency insurance fund to separate it from dependency due to other risks, like in Germany, Austria and Japan.

Other countries are introducing incentives to promote informal care like providing state-funded compensation for people who take temporary leave from their job to take care of a loved one. Elsewhere, such as in France, the United States and Singapore, dependency can be financed by cashing in on the value of the person’s home, with the financial income they can make from property, including reverse mortgages. Lastly, private dependency insurance (paying into a system to cover any dependency costs) is a small market in Switzerland but likely to expand. "In the United States, where this system is more developed, children encourage their parents to take out this type of insurance. Dependency costs can seriously eat away at an inheritance," Mr Courbage says.

In addition to the practical issues involved as people live longer lives and reach very old age—a condition that varies with each person and culture—we still must grasp and integrate what it all means. The French anthropologist Frédéric Balard emphasises the multiplicity of reality depending on the period, culture and economic conditions.

Some societies honour centenarians, like in Japan, where they are referred to as "living treasures". However, in other realities, they are sacrificed.

As in the film The Ballad of Narayama, which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983, set in a poor, isolated village in the 19th century, people who reached the age of 70 were meant to go the peak of Narayama mountain to die willingly, a tradition called ubasute. Our prosperous and technologically advanced society is capable of extending human lifespan like never before. Making sure that the value of this fourth age is properly recognised, and that the people who go through it are supported, appreciated and listened to, while not denying them their old age, as with the fantasy of transhumanism, are some of the most compelling ethical challenges faced by humanity.

To evoke the ages of life shown on the cover, various tests of paper cut inspired by topographic representations have been made.

Une catégorie inventée dans les années 1980 pour parler des seniors âgés sans qu’elle définisse un âge précis.

Costs of home care, while costs of long-term care facilities come to 8,000 million.

The oldest person living in Switzerland, Alice Schaufelberger-Hunziker, who lives in a facility in Winterthur and celebrated her birthday in January 2019.