There is still has a major gap in Switzerland between the number of people waiting for a transplant and the number of available organs. A popular initiative wants to turn every adult into a potential organ donor, supporting the system of presumed consent. But is that the right way forward?

At the end of 2017, 1,478 patients were on the waiting list in Switzerland to receive an organ, in most cases a heart, lung, kidney or liver. At the same date, 594 patients had received an organ. And 75 people died waiting for one. In terms of the number of deceased donors per million population, Switzerland’s score is mediocre compared with other countries: 17, versus 44 in Spain and 28 in France.

To change that, the Swiss Federal Council initiated an action plan five years ago to raise the deceased donor rate per million population from about 13 in 2013 to 20. “The campaigns led by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health are a step in the right direction. But we need to target more young people and seniors, who think they can no longer donate their organs,” says Philippe Eckert, chief of the Service of Adult Intensive Medicine at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) and head of the Latin Organ Donation Programme, a network initiative in French- and Italian-speaking Switzerland.

Organs are removed from two-thirds of patients with brain death or, for the past few years, cardiac arrest. “When a person is brain dead, we have to ask family members how they feel about organ donation. In the vast majority of cases, these relatives, already upset, have no idea and would rather refuse donation,” Philippe Eckert says.

Swisstransplant, the Swiss National Foundation for Organ Donation and Transplantation, estimates that 80% of the Swiss population say they support organ donation but do not express that choice to their loved ones. That reality would explain the low donor rate compared with France and Spain, where donor consent is presumed if the individual has not opted out of organ donation by signing a register. A popular initiative was launched a few months ago to introduce the principle of presumed consent into Swiss legislation (see point 3).

Read our interview with Manuel Pascual

Évelyne Savary spent two and a half years on a ventricular assist device (VAD) before receiving a heart. “I experienced wonderful times and pure happiness because I was able to regain much of my independence with the VAD. But there were also difficult times of course. My motto was: patience – trust – courage – positive thinking. The wait prepares us for the transplant, which is an extraordinary gift of life. Every day I think about my donor, who remains anonymous, but without whom I would no longer be here.”

Patients have to wait so long due to the shortage of available organs but also to the lack of compatibility between the donor and recipient. “Organ allocation depends on many factors that are different for each organ,” says Manuel Pascual, chief physician of the Service of Organ Transplants at CHUV and medical director of the Transplantation Centre in French-speaking Switzerland. “For a kidney, time spent on the waiting list is a key factor, along with genetic and other individual criteria. For a liver, the seriousness of the patient’s condition will determine where he or she stands on the priority list.”

According to Swisstransplant statistics for 2017, the average waiting time is 142 days for a lung and 1,042 days for a kidney. That difference is due first to the sheer number of kidney patients, and second to the fact that dialysis can keep people alive while waiting. “As for other vital organs, the person could die if they don’t receive an organ after a certain time,” Manuel Pascual says.

Claude Reymond, 65, talks about his kidney transplant as a release. It allowed him to take back the life of fairground he loves so much.

Letting others live. Saving a life by giving someone an organ they cannot live without. These are the most frequently cited reasons why donors donate. For now, Swiss law requires explicit consent. Under this system, donors can express their decision to “opt in” by signing up for a donor card, registering on the smartphone app Echo112 or by leaving written or verbal instructions with their loved ones.

But consent is not always clearly expressed. Delphine Carré coordinates organ donations and identifies potential donors at CHUV’s intensive care unit. “In cases of brain death or when no therapeutic options are left to save a patient, we can approach the subject of organ donation with the family. If the deceased has not left clearly identified consent, we ask relatives what the person’s decision might have been. We do it with a lot of tact and sensitivity as we know they’re going through a lot of pain,” the nurse explains.

In most cases, the family does not know what the deceased would have wanted.

“Talking about one’s own death and organ donation is taboo in our societies. And if in doubt, when the individual hasn’t expressed any clear position, their loved ones would rather refuse than get it wrong.”

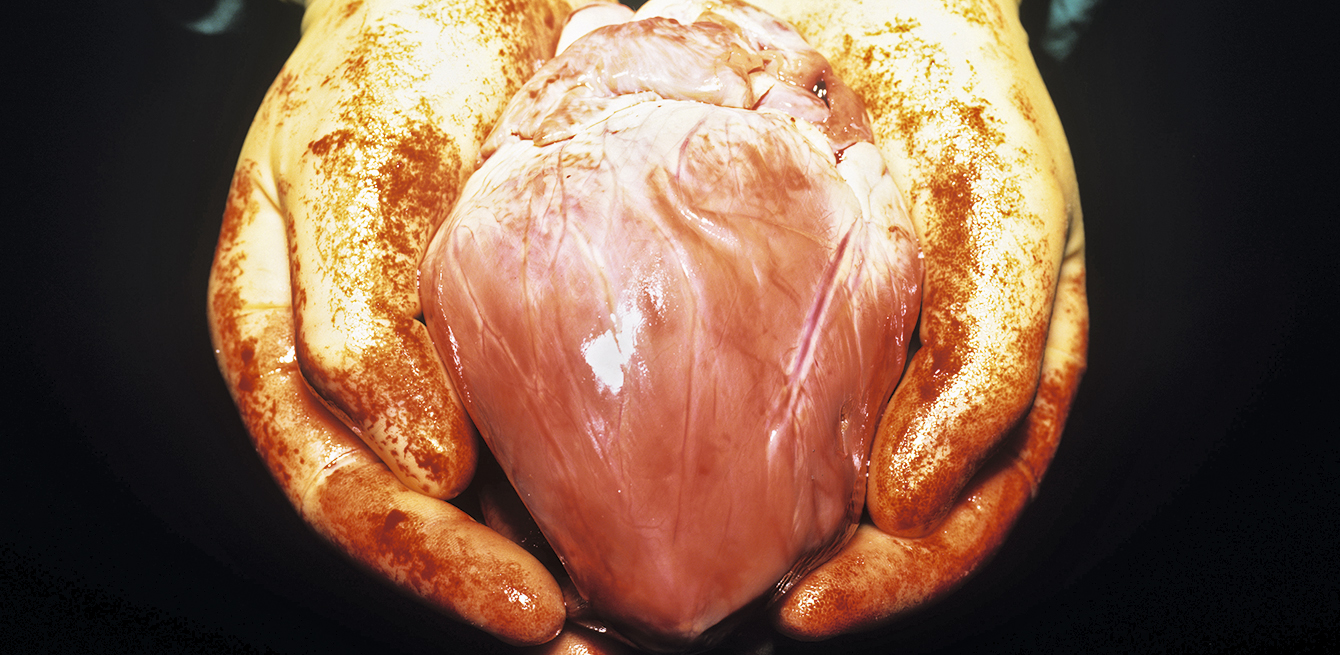

Others say no for religious reasons. Delphine Carré also mentions the negative image of organ harvesting. “Families fear that the body will be mutilated or disfigured.” But the operation is the same for a transplant on a live patient. “The person from whom organs are removed is not just a body,” says Claire Peuble, donation and transplant coordinator at CHUV. “We take care of them and guarantee respect for bodily integrity.”

Consent can be hard to obtain. In these cases, talking about it and explaining the procedure of organ donation quell any doubts and give people time to decide. “We answer all questions from the family to reassure them,” Claire Peuble says. “We also guarantee that any organ removed will be transplanted.”

When a family does agree, it is usually because they think that is what the person would have wanted. “Once consent is obtained, the donor’s organs are preserved with mechanical equipment and drugs. We also run specific biological and radiological exams to check the health of each organ so that it can be safely transplanted into the recipient. Due to the tight time constraints, we look for and call in compatible recipients at the top of the priority list. Donation and transplant are performed in parallel before the donor’s body is delivered to the family for funeral arrangements.”

The decision is even more difficult when it involves the death of a child.

“That kind of thing is not how life is supposed to be,” Delphine Carré says. “Parents who agree to donate a child’s organs do so to bring some meaning out of such an unjust death.” Letting her emotion show, the nurse remembers the parents who did not want to donate the heart of their child. “It was too symbolic for them, this organ synonymous with love.” A colleague also remembers a mother who wanted to hear her child’s heart stop. “We let her listen to the heartbeat until the end.”

The decision whether to donate the organs of a family member is difficult, but the situation also affects healthcare providers. “These procedures are not so common in the Service of Intensive Care at CHUV,” Delphine Carré says. In 2017, organ donations were made in 22 cases out of a potential 40.

“Emotion is high for the healthcare and operating room staff. Unlike traditional care, where the purpose is to treat, here the patient is clinically dead. Only blood circulation is kept functioning to preserve the organs,” Claire Peuble explains.

The body is taken to the morgue when it comes out of the operating room, and the staff is not used to that.

In October 2017, the Jeune Chambre Internationale de la Riviera, an organisation of young citizens, launched a popular initiative to promote organ donation and make a presumed consent system the law.

Everyone living in Switzerland would then become a potential donor, unless the individual refuses during his or her lifetime. Essentially, that means that individuals who object to donation would have to sign a national register to express their opposition. But donation would not be automatic. Even if the deceased person is not on the register, the family would have to be contacted before any decisions are made. That is similar to the system in France (see inset below).

France has had a presumed consent system in place since 1976. In practice, doctors routinely ask next of kin about the intentions of the deceased. The result is that about one-third of donations are refused, most often because those asked object to it. Amendments to the law passed on 1 January 2017 aim to align better with the wishes of the deceased. French citizens opposed to donating their organs can opt out by signing a national register. Otherwise, their organs will be donated, unless those close to the deceased prove the specific circumstances for refusal expressed by the person in a written and signed document. “Next of kin can submit a written or oral document prepared by the person before their death,” says Olivier Bastien, director of organ donation and transplants at the French Biomedicine Agency, in an interview with RFI. This measure, presented by Parliament members as a way of increasing the number of transplants, got the medical community worried, reports the French newspaper Le Monde. The French National Order of Medical Doctors and organisations supporting human tissue and organ donation fear distrust from families, who will, paradoxically, go against wishes to donate organs.

Swisstransplant supported the initiative, donating 30,000 Swiss francs. “This is a very important issue, and our foundation believes that we need greater safety and clarity to respect the wishes of the deceased,” says Franz Immer, a cardiovascular surgeon and Swisstransplant’s director. He feels that the initiative would relieve both families and medical staff.

Next of kin is currently responsible for making the decision to donate organs, a practice that Franz Immer says is “problematic”. “As part of the action plan launched by the Swiss Confederation and cantons in 2013, we noted that, despite major progress in hospitals, 60% of the families asked objected to donation. The conclusion from doctor interviews was that the family often refuses because they are unsure of the wishes of the deceased.”

Jozo Nevistic did not hesitate for a moment to donate a kidney to his son to save him from the disease.

A presumed consent system for organ donation has already been rejected by Swiss parliament several times. A two-thirds majority of the Swiss National Council supported the introduction of such a system in 2015, but the bill never passed the Council of States. One of the arguments put forward by opponents within the National Council was whether “society as a whole had a right over organs”. Before taking any additional measures, some Parliament members also wanted to wait and see the results of the action plan, which is in effect until the end of 2018.

The Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics opposed presumed consent in 2012 on the grounds that the system risked infringing on people’s rights. It then highlighted the lack of empirical data showing that the model would truly increase the number of donors. However, the Commission has since decided to review the issue again, as indicated on its website.

Nikola Biller-Andorno, Professor and Director of the Institute of Biomedical Ethics at the University of Zurich, believes that presumed consent is not “immoral”, but “it might not be the best solution from a political viewpoint.” Such a change could make the Swiss feel forced into it.

For French philosopher Valérie Gateau, the main question today is the return to daily life after the surgery.

/

The percentage of people who have filled in their donor card in Switzerland.

/

The percentage of people who object to donate organs after the death of a family member.

/

The donor rate per million population in Switzerland in 2017.