Rare health disorders affect 7.2% of the Swiss population. More research and treatments are needed. Patients and the medical profession are fighting to change that.

“As many people suffer from a rare disease as from diabetes in Switzerland. For diabetes, you have specialists, associations and treatments available in a flawlessly organised network. But that’s hardly the case for rare diseases.” Anne-Françoise Auberson, the president of ProRaris, fully under-stands that the fight to gain recognition for rare diseases is relentless. The umbrella organisation she heads criticises the neglect which these diseases frequently receive from the medical community, and the real headache this represents. Not enough patients with each disease, or enough experts, scant research.

“Whatever their disease, patients never have enough information,” she says. “It takes 5 to 30 years to diagnose the disease and 95% of rare diseases have no treatment available.”

Rare diseases have slowly been gaining recognition over the past 10 years or so in Europe. On the impetus of patient associations, national plans have been mapped out to bring these isolated disorders on equal footing with more common diseases. In Switzerland, rare diseases were the subject of a postulate submitted before Parliament in 2011. In 2014, the Swiss Federal Council introduced a rare disease policy as part of its Health 2020 strategy. Implementation was set for 2017 but is already two years behind schedule. This does not come as a surprise with all the challenges involved, such as opening expert centres, providing patients with more information and better care, raising awareness, improving psychosocial integration, financing research, etc. A long, bumpy road lies ahead.

A disease is classified as rare if it affects less than one out of 2,000 people worldwide. Between 6,000 and 8,000 currently exist. Some of the more widely known ones include cystic fibrosis, forms of amyotrophy and certain forms of leukaemia. Others are more obscure. “Genetics makes you a powerful human being,” says Andrea Superti-Furga, chief of the Genetic Medicine Service at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). “But all it takes is just a tiny little change in letter in a DNA sequence to destroy you on the spot. A small cardiac or pulmonary malformation or lack of a single enzyme can cause irreparable harm.” Eighty percent of rare diseases are genetic. They can be chronic, degenerative and even fatal.

One of the first obstacles is to identify the disease accurately. Having to go from doctor to doctor, waiting for a relevant diagnosis, is often due to the lack of expertise. “Patients describe their often long list of symptoms that are not directly related to each other,” Dr Superti-Furga says. “That makes diagnosis long and complex. It requires a special form of sensitivity to identify a rare disease.”

“Genetics makes you a powerful human being,” says Andrea Superti-Furga, chief of the Genetic Medicine Service at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). “But all it takes is just a tiny little change in letter in a DNA sequence to destroy you on the spot. A small cardiac or pulmonary malformation or lack of a single enzyme can cause irreparable harm.”

Eighty percent of rare diseases are genetic. They can be chronic, degenerative and even fatal.

One of the first obstacles is to identify the disease accurately. Having to go from doctor to doctor, waiting for a relevant diagnosis, is often due to the lack of expertise. “Patients describe their often long list of symptoms that are not directly related to each other,” Dr Superti-Furga says. “That makes diagnosis long and complex. It requires a special form of sensitivity to identify a rare disease.”

Rare diseases are part of everyday life in paediatric units. And they come with a unique set of needs and challenges. “Drugs used to treat rare diseases can generally be administered starting at age 12, 16 or even 18,” says Michaël Hofer, senior physician in charge of the paediatric immunology and rheumatology unit in French-speaking Switzerland. “But there is not enough specialised literature to allow us to prescribe certain drugs for our young patients. So we have to negotiate with insurance companies to get them to reimburse the treatment.”

Another challenge is the transition of young patients into adult patients. “Teen years are a difficult time. At this age, patients often reject their illness or refuse to take their treatment. They hope that by not thinking about it, the disease will go away,” the paediatrician says. Dr Hofer organises consultations with the adult specialist to make sure the transition goes as smoothly as possible. “We do that to build the patient’s trust in the new doctor and make sure the medical records are transferred properly.” An international team has recently devised a transition checklist aimed at the different paediatric services to improve these transfers. For example, as of age 12, the doctor is advised to discuss the disease with the patient to make sure they understand everything involved.

When they can’t, doctors address each symptom separately, relieving pain and treating deficiencies. “General practitioners often take a long time before referring patients to the right specialist, sometimes due to a lack of information, sometimes out of pride,” the geneticist says. Doctors sometimes even diagnose mental issues. “Psychosomatic problems are indeed common, but it’s awful for a person truly affected by a rare organic disease to be labelled with a psychosis.”

An accurate diagnosis always comes as a relief. “A medical explanation is a way of finding out where the real blame should go. It triggers the psychological process that eventually leads to acceptance of their illness,” the physician says.

In the 1950s, genetic disability was sometimes attributed to “the father who was drunk when the child was conceived. These shameful explanations are still floating around in the back of people’s minds.”

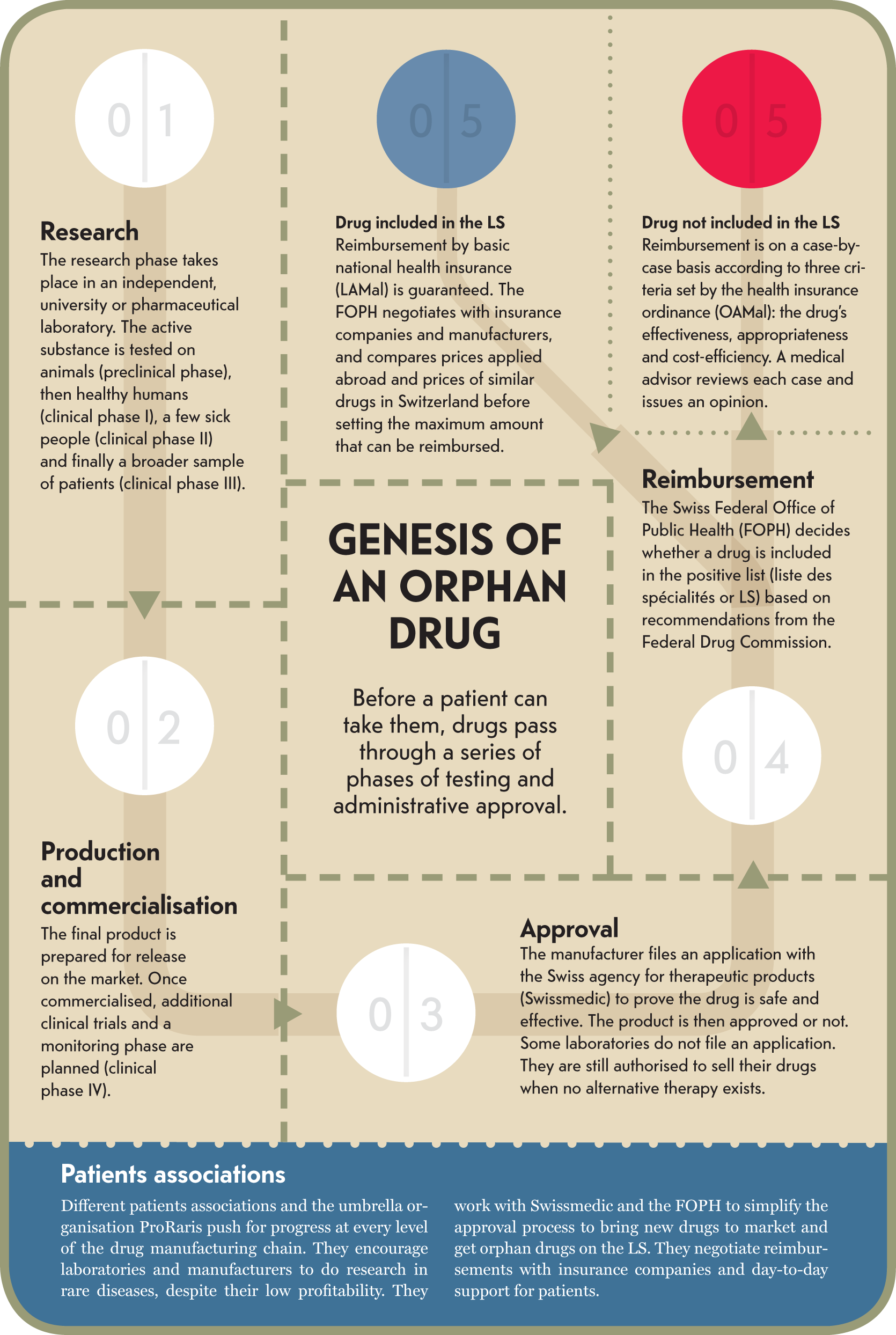

Medication used to treat rare diseases is also rare, as demand is low. To stimulate the market and research, the Orphan Drug Act passed in the United States in 1983 introduced incentives, offering “orphan” drug manufacturers tax breaks and a multi-year monopoly. In Switzerland, similar advantages are granted to pharmaceutical companies that develop these drugs. For example, the process is simplified and less costly to bring drugs to market, and less scientific red tape needs to be submitted to Swissmedic, the Swiss medical watchdog that monitors the market for therapeutic products.

“Orphan drugs used to treat rare diseases are extremely expensive, and that’s not going to change. What we have to do is find a human way of reimbursing them.” Anne-Françoise Auberson blames insurance companies that baulk at the idea of reimbursing costly treatments.

But the price of orphan drugs is hotly debated. Interpharma, the organisation that represents Swiss pharmaceutical companies, says that the sales price is high because production costs are high. That assertion is based on a study by the Office of Health Economics, a British healthcare research and consultancy institute, estimating it at 1.3 billion Swiss francs.

Others in the industry say that is much too high. “That figure is hugely exaggerated, especially if you factor in the incentives granted with the status of orphan drug,” says Andreas Schiesser, head of the drug project at the organisation Santésuisse. “Prices aren’t based on research costs but on expected benefits of the drug for patients.”

Olivier Menzel, president of Blackswan, a foundation specialised in research on rare diseases, agrees:

“The most costly stage in developing a new drug is the clinical trials. But with rare diseases, there are so few patients to start with that costs are automatically lower.”

Meanwhile, Interpharma points out that the 1.3 billion Swiss francs is an average, and stark differences exist depending on drug indications. But the organisation doesn’t provide any specific figures for orphan drugs. Menzel says, “We also have to be careful not to put too many restrictions on manufacturers by capping prices. Firms should continue investing in research for rare diseases. But everyone, both manufacturers and insurance companies, should play their part by setting reasonable margins.”

With such high prices, orphan drugs that are not included on the positive list (liste des spécialités or LS), established by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, are not systematically reimbursed by health insurance (see infographic). Research on rare diseases, being limited in terms of patients and specialists, does not always meet the strict criteria for inclusion. Health insurers refer to the criteria set out in Switzerland’s health insurance ordinance (OAMal) to decide whether to reimburse a drug. The treatment must be effective, appropriate and economical. “Unfortunately, when pharmas raise the price of a drug, some insurance companies refuse to reimburse it, but these treatments are often vital for patients,” Anne-Françoise Auberson laments.

Even health insurance providers realise how complex reimbursement is. “Some special cases are tough to assess,” Andreas Schiesser says. “When a disease is not fatal, and the pain and inconvenience are relative, where should we draw the line? Reimbursing overpriced treatments is not fair for other patients.” Meanwhile, health insurers readily shift the blame to drug manufacturers. “Take the case of the drug used to treat porphyria (a rare metabolic disorder). The Australian laboratory that developed the treatment didn’t even file the approval application with Swissmedic, which would simplify the procedure for reimbursement,” Santésuisse says.

Infographic : Genesis of an orphan drug

Reforms to the health insurance ordinance, in effect since March 2017, have improved the care provided on a case-by-case basis, the president of ProRaris says. If a request comes in from the general practitioner, the insurance company has to consult its medical advisor and issue a response within two weeks.

“That’s progress, but treatment differs between cantons, and it’s still hard to find experts capable of giving a well-informed opinion,” Auberson points out.

“Patients have taken things into their own hands to come out of their isolation and demand rights,” Anne-Françoise Auberson says. “Rare diseases have been brought to the attention of policymakers thanks to intense lobbying efforts.”

As a result, the Federal Council came out with a plan to implement the national concept for rare diseases in 2015. The backbone of the project is the implementation of expert centres. These hubs located throughout Switzerland are to be set up by type of disease to pool the right expertise and enhance synergies. “We want to create teams of different specialists, cardiologists, lung specialists, psychologists and especially geneticists,” says Loredana D’Amato Sizonenko, coordinator of the Orphanet website in Switzerland, a partner in implementing the national policy (see inset). “Some organised care is already available. Now we just have to get all those involved to agree so that this expertise is distributed strategically.”

Some 6,000 health disorders are listed on the information website on rare diseases for French-speaking Switzerland (www.info-maladies-rares.ch). This platform set up in 2013 by CHUV and HUG provides useful information including the care services available in the region for each disease. Patients and specialists can also seek assistance using the website’s hotline. Loredana D’Amato Sizonenko is in charge of the platform for HUG and covers its coordination aspect. “We work with specialists and encourage them to work together. When collecting information, we sometimes realise that two areas of expertise are working on the same issue without talking to each other. The idea is to improve collaboration and make their work visible to others.” The website for French-speaking Switzerland collaborates closely with the Swiss branch of Orphanet, an international platform that provides useful information about managing rare diseases in about 40 countries, including Switzerland.

Under the supervision of the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, a wide range of organisations are part of the implementation of this national policy: the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, university hospitals, the board of healthcare directors representing cantons, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the umbrella organisation representing patients ProRaris and the platform Orphanet.

“The implementation of the concept is falling behind schedule,” Auberson says. “Lots of interests are at play. ProRaris, which defends patients, is just one of the many sides. I hope its voice will be heard.”

The associate medical director of CHUV, Jean-Blaise Wasserfallen, is confident and believes in the network set up by the university hospitals in French-speaking Switzerland. In 2013, the CHUV and Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) implemented a joint strategy, which led to the creation of a website on rare diseases (see inset). “The point of this collaboration was to bring down the barriers that prevent doctors, patients and the public from having access to the information they need.”

The associate medical director is sure that progress will be made in the region. “We compare our different departments based on specific, quantitative criteria: how many patients are currently being treated, what expertise is involved on both sides, are we publishing in scientific journals on the subject, and so on.” For example, in 2013 CHUV opened a centre specialised in molecular diseases, recognised, along with the centre in Zurich, as highly specialised medicine. It is gaining recognition as a provider of expertise in the area.

“We are supposed to proceed based on the gentlemen’s agreement for the network of expert centres in Switzerland, i.e. based on the expertise already available at each hospital. I can’t wait to see how that will work out in practice.” The idea is for these diseases gradually to be rare only in terms of prevalence but not neglected in terms of care and treatment. ⁄

Maximum number of people

affected by a disease for it

to be classified as “rare”.

Number of rare diseases

in the world.

Number of people with an orphan disease in Switzerland.

Source: Proraris and Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2017

Scientists and doctors have been talking about rare diseases for only the past 20 years or so. These neglected diseases have gone from a total lack of expertise to the introduction of a national concept, and are slowly carving out a place for themselves in Swiss medicine and healthcare.

Orphanet website established

in France. First online encyclopaedia of diseases and specialists.

Switzerland

joins the

Orphanet consortium

and begins classifying expert centres in

the country.

ProRaris founded, an umbrella organisation for patients.

First rare disease awareness day held in Switzerland. The same year, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court ruled in favour of a health insurer in its decision not to reimburse a patient with Pompe disease. Politicians get involved in the issue. Ruth Humbolt from the Christian Democratic People’s Party submitted a

postulate before Parliament.

The university hospitals in Geneva and Lausanne (HUG-CHUV) launch a strategy spanning French-speaking Switzerland with

the website for rare diseases. The two hospitals evolve into expert centres.

The Ice Bucket Challenge contributed to raising awareness about amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

A number of celebrities participated in the

event widely covered

on social media, raising

$100 million.

Deadline set for the implementation of the National Plan for rare diseases. The project is running two years behind schedule. A national coordination team has been set up to address the situation.

1/8,000 to 1/10,000 depending on the country

Genetic

Digestive and respiratory issues, abnormal secretions and infections in the bronchial tubes and pancreas

No cure

1 to 5/10,000 depending on the country

Inadequate production of fibrillin, a protein found in connective tissue

Gradual dilation of the aorta and risk of rupture, heart failure, stretch marks, ocular complications

Multidisciplinary care

1/10,000 to 1/20,000 depending

on the country

Genetic

Fragile bones and sometimes bone deformation, fractures

Orthopaedics and physiotherapy

1/20,000

Genetic

Gradual muscle paralysis, deterioration of motor neurons, respiratory failure

No cure, symptom management and palliative care

1/20,000

Unknown, genetic factors suggested

Chronic fevers, early onset of arthritis, systemic inflammations

Mainly anti-inflammatory medicine

1 to 9/100,000 depending on the country

Unknown

Obstruction of bile flow in infants, which leads to cirrhosis within a few months

Surgery or liver transplant