With the increasing use of social media, young people receive a lot of information about sex, some of it pleasant and educational, but sometimes false or inappropriate. To answer their questions, sexual health experts take a positive approach.

On its release, season 3 of Sex Education shot to top the list of the most watched series on Netflix. This series from the United Kingdom is about a teenage boy, Otis, who sets up an underground sex therapy clinic in the school gym. With humour and empathy, the show deals with many facets of teenagers’ sex life and love life. “The series is the perfect example of positive sexuality,” says sexual health teacher Véronique Martinet, from the Vaud-based foundation Profa.

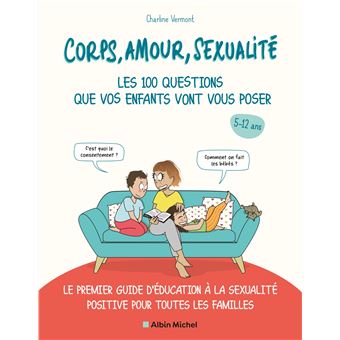

The popular Instagram account “Orgasme et moi” (with nearly 600,000 followers) stems from the same mindset. Its author Charline Vermont, who is French, has published one of the first French-language guides to positive sex education entitled Corps, amour, sexualité : les 100 questions que vos enfants vont vous poser (Body, love, sexuality: the 100 questions your children will ask you). Published in September by Albin Michel and approved by a committee of experts, the book has already sold 50,000 copies.

In the Interdisciplinary Division for Adolescent Health (DISA) at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), this sex-positive approach is applied as a standard to sexual health consultations. “First of all, participating in an interview is voluntary, free and confidential,” says Anne Roulet, who sees young people aged 12 to 21. Participants come solo or with their partner. “Next, it’s important not to be judgemental and treat the person with empathy. Inclusiveness is also important. Through words, attitudes or even the posters we put on the walls, we show that we can talk about what’s normal just as well as what’s not normal, especially in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity.”

“Positive sexuality” has become so ubiquitous – in the media, on TV shows, in politics or in literature – due to various factors, says Caroline Jacot-Descombes, sex education project leader for the organisation Santé sexuelle suisse. “Social protest, such as Switzerland’s nationwide feminist strike in 2019 and the #MeToo movement, play an important role.

The trend towards personal development, which encourages people to explore who they are as individuals, also contributes to this.”

On a more institutional level, it was not until the 2000s that the work of organisations began to align with government demands. “The declaration of sexual rights presented in 2008 by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) was a real turning point,” says Caroline Jacot-Descombes. “Before that, the Swiss Confederation and the cantons provided to promote, respectively, sex education, under risk prevention mandates, and to prevent STDs, unwanted pregnancies and violence. These days, they realise how important (and effective) messages can be about discovering one’s body and sexuality in all its diversity.”

The same is true for consultations at the CHUV. “We have moved away from a risk-oriented approach in terms of healthcare to a more holistic approach to health,” Anne Roulet says. “The aim is help young people know what they want, know their body and their sex organs, be able to name them, and realise how beautiful they are, so that they can give pleasure to themselves and to others. In this way, they can learn to consent (or not), because they better understand their limits and potential better.”

Has this pervasive sex-positive content changed today’s youth? Sexual and reproductive health educators Séverine Chapuis and Véronique Martinet have been working for Profa for some 20 years. The foundation has been mandated by the canton of Vaud to provide five 90-minute sex education classes, spread out over the course of compulsory schooling from age 6 to 15. Both experts have observed that people feel they can speak more freely.

“Young people have integrated the distinctions between biological sex, gender identity, gender expression and sexual and emotional orientation. They are also familiar with concepts such as polyamory.”

Anne Roulet also notes that the young people who come for consultation at the DISA are generally more informed. “They have more knowledge related to orientation, gender identity, practices, and feminism. The word consent, for example, is much more present than it was 10 years ago, for both girls and boys. I believe that’s a big step forward.”

But their concerns remain more or less the same. “The average age at which young people first become sexually active has remained unchanged for nearly 30 years at 17 and a half,” Séverine Chapuis points out. Anne Roulet agrees about a degree of continuity in the topics discussed. “Young people want to know if they’re normal, how to kiss, what they’re supposed to feel when they’re in love, what happens during sexual intercourse, why it hurts in one position or another, etc.”

“Although kids communicate differently, more via smartphones these days, relationship basics are often the same,” say Yves Cencin and Carol Navarro, a health promotion and education consultant team that works with schools in the canton of Geneva (for the Department of Public Education, Training and Youth). “Young people can sometimes be mushy, sometimes unsettling, sometimes even crude.”

Internet is not just a medium for delivering helpful content to young people; it also facilitates access to pornography. “With the increasingly common use of the internet and smartphones, young people are flooded with sexual information and images that stimulate their brains, showing them things that they didn’t necessarily want to see,” Véronique Martinet says. “It’s difficult for them to escape this type of content.” This topic is discussed in sexual health classes and consultations. “Pornography is implicit in their questions, for example when they ask about a sexual act typically seen in pornographic films,” Yves Cencin says. “Young people also sometimes use inappropriate language, or ask outright, in a provocative attitude, ‘what’s their best porn site?’” says Séverine Chapuis.

Questions about performance often reflect experience with pornography. “We’re sometimes asked, ‘If I have sex, should I perform fellatio or sodomy?” Séverine Chapuis says. “In that case, our answer is very clear: ‘In love and in sexuality, nobody forces you to do anything.’” The educators remind us that consuming pornography is illegal in Switzerland under the age of 16. “We don’t totally demonise it either. We explain that pornography is used to excite someone sexually, that it could be part of their adult life in the future.”

In Anne Roulet’s consultations, anything that is a source of pressure or stereotypes is broken down, especially pornography. “Pornographic films perpetuate stereotypes. Even in traditional cinema, heterosexuality is often simplified as kissing, the man undressing the woman, penetration and orgasm.” The sexual health counsellor with the DISA at the CHUV regularly talks to young people about how pornography is made. “These films often show one type of vulva, one type of penis. It’s all about revealing the special effects, explaining how the genitalia are shiny, the testicles stretched out, why the erections last so long.”

Group classes usually include a Q&A session. “Young people receive a lot of information. Some of it’s true, some of it’s false,” Carol Navarro says. “That information comes from the internet, but also – like in the old days – friends, family members, etc. We provide them with scientific knowledge and tools. And together we break down some preconceived notions ideas about sexuality and relationships.” /

Parents, friends and other family members are involved in teaching their children about sex, in addition to what they learn in school.

Below are a few points of reference on this subject:

From age 0 to 6, parents can name the child’s private parts, take a positive attitude towards allowing children to discover and explore their own body, and introduce the notion of consent. An open attitude to the diversity of sexuality and gender is also recommended.

Book: Elephantine, Renardo et Charlie (in French)

From age 6 to 12, adults are encouraged to explain the initial signs of puberty, discuss different lifestyles, and respect the child’s need for privacy.

Book: Guide du zizi sexuel (in French)

From age 12 to 15, it is advisable to start talking about how they relate to their body and their self-image, respectful relationships with others, especially on social media.

at home

It is also important to inform them about the menstrual cycle, contraception and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases.

Brochures: Hey you, Mon sexe&moi

For young people age 11 to 20. The website ciao.ch offers information and advice, and is a place where young people can ask their questions about sexuality and experts answer them within two days. They can also view questions – all of which are anonymous – asked by other users and the answers provided.

For parents of children age 0 to 18. The website educationsexuelle-parents.ch provides information about how to talk about sexuality within the family and contact information for centres where parents and children can get advice.

Corps, amour, sexualité : les 100 questions que vos enfants vont vous poser - tome 1 (édition 2021)

The organisation Santé sexuelle suisse defines sexuality as “a central and positive aspect of being human, which encompasses sex, identity, (gender) roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, desire, intimacy and reproduction”.

The World Health Organization integrated the positive dimension of sexuality into its definitions in 2006.

“Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity.”

The WHO also defines sexual health as a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.