A swiss researcher is developing a battery-free pacemaker with a mechanism based on the automatic wristwatch.

The 65-kg Alpine sheep lay motionless on the operating table, under anaesthesia. The researchers moved it onto its right side. Then a surgeon delicately made an incision into its chest wall and attached a small, round gold-coloured device to the animal’s beating heart.

Adrian Zurbuchen, a brainy-looking, brown-haired young man, anxiously watched. It was the first time that the prototype he had just developed was being tested on a live animal. The University of Bern researcher wanted to create a battery-free pacemaker that worked using a mechanism inspired by automatic wristwatches. The energy harvested from the heart’s motion is what charges the instrument.

One hour later, Adrian Zurbuchen felt relief. His experiment was a success. The sheep’s cardiac activity generated a constant electric flow of 16 microwatts, enough energy to power a basic pacemaker.

Since this initial test was performed in April 2010, the 34-year old researcher has conducted a number of other trials and developed a more sophisticated prototype. “We tried the system on pigs,” he says. “We are now looking for a company that can finance our research and develop the product for commercial use within the next two to three years.” His next step is to integrate his self-charging system into an operational pacemaker.

Since this initial test was performed in April 2010, the 34-year old researcher has conducted a number of other trials and developed a more sophisticated prototype.

Zurbuchen’s device resembles a bare watch, with no face, external components or bracelet, but is equipped with fine wiring. The system boasts the advantage of lasting longer than traditional models. “A pacemaker generally lasts six to twelve years,” he says. “A Swiss timepiece mechanism can last 20 years without repair.”

By changing the system, he believes that it could even work for 30 or 40 years. “Our mechanism is simpler than that of a watch, because it does not need to be aesthetic or tell time,” he says. “The device would also be operating in a protected environment with a stable temperature,” i.e. inside the human body.

Martin Fromer, a cardiologist specialised in pacemakers at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), believes that this innovation would be especially useful for young patients with heart conditions. “When a 12-year old child develops heart disease, we try to replace his or her pacemaker as rarely as possible,” the expert says. “Those are rather complex operations.”

Adrian Zurbuchen’s instrument would also reduce the size and

Adrian Zurbuchen’s invention highlights the potential of applying watchmaking expertise to medical technology.

weight of pacemakers in general. “The battery is often what takes up the most space in the device,” he says. Another advantage is that the contraption would be placed directly on the patient’s heart. This eliminates the need for the leads that link the pacemaker to the heart muscle, and

in doing so, makes it more reliable.But the road lying ahead for the researcher is not without obstacles. “An automatic watch is strapped onto the wrist and self-winds with the movement of the arm, which is different to the motion of the heart,” he explains. “We are trying to develop a system that best harnesses heartbeats. For several years, we have been analysing these movements to create the best absorption mechanism.” Complicating things, a sick heart does not necessarily beat regularly. “The irregularity of heartbeats could prevent the device from charging.”

Adrian Zurbuchen’s invention highlights the potential of applying watchmaking expertise to medical technology. “The two fields share many similarities,” notes Simon Henein, who holds the Patek Philippe Chair in Micromechanical and Horological Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL). “Both surgeons and watchmakers work on a tiny scale and have to be extremely precise. These specialisations are also part of the same economic fabric. We have the same sub-contractors and use the same materials.”

Luc Tissot, former chairman of the eponymous group, is one of the watchmakers who took advantage of this potential early on. Back in 1978, he used the expertise of his employees at his factory in Le Locle to produce pacemakers in collaboration with the pharmaceutical giant Roche. “We had to work with various metals at different temperatures. There were many technical constraints, and manufacturing a pacemaker has to follow a rigorous process,” Luc Tissot says. The product resulting from this collaboration has since been bought by the Swiss company Intermedics.

More recently, Luc Tissot has founded a new start-up, Tissot Medical Research. The company has developed a contact lens that measures intraocular pressure to detect the first signs of glaucoma. “As in watchmaking, it involves a miniscule object,” the entrepreneur says. “We placed a sensor on the lens to measure eye pressure every time the patient closes their eyelid.” The device is expected to be available on the market within the next two years.

Despite this handful of examples of synergy between watchmaking and medicine, partnerships between the two fields remain too rare. “The design of medical devices is regulated by very strict standards, which watchmakers are unfamiliar with,” Luc Tissot says. “It is very complicated, or even impossible, to develop a product without first forging a partnership with a medical company.”

However, Charles Baur, in charge of medical microtechnology of the Patek Philippe Chair at the EPFL, believes that watchmaking and medicine will soon work together as never before. “Connected watches have huge potential in medicine,” he says. “For example, a surgeon could check patient data in the middle of an operation simply by looking at his or her wrist, while remaining focused on the patient. That would be fantastic.”

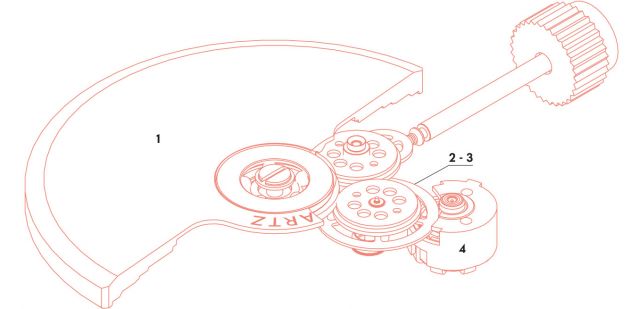

1.The motion of the heart sets off the oscillating weight, which starts moving.

2. A mechanical rectifier converts this movement into a rotation that turns in one direction.

3.The rotation winds a mechanical spring.

4.Once fully wound, the spring unwinds and charges

an electric micro-generator.

5.The generator powers an accumulator used

to store the electricity generated and produce a continuous flow of energy.

6.The accumulator in turn powers an electric circuit that provides energy for the pacemaker.

The Patek Philippe Chair in Micromechanical and Horological Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EFPL) is working with the measuring systems manufacturer Sensoptic SA to develop new surgical instruments that are useful to both watchmakers and doctors. “Watchmakers, like doctors, work on a scale that is so small that they can no longer feel the surfaces they press on,” says Charles Baur. “We are developing surgical instruments that would measure the pressure applied by a surgeon to a patient’s eye during corneal surgery.”