About one in five teens and young adults is forced to cope with moderate to severe acne. But solutions increasingly targeted treatments exist to fight the disease.

Good skin”, “luminous”, “bold glamour”: these filters with inspiring names are increasingly common on social media. Applied to faces taken in photos or filmed, they give completely smooth skin without a single mark or stain. The almost unreal appearance and complexion of influencers on TikTok, the social media used by 34% of under-18s in Switzerland, are in stark contrast to the everyday reality that young people experience. In fact, 75% to 90% of them have varying degrees of the inflammatory skin disease called acne vulgaris. It is estimated that around 20% of them even suffer from a moderate to severe form and that 1% of girls and 3% of boys get more severe forms.

“When you have acne, you often suffer from a significant drop in self-esteem, which can influence latent or underlying depression,” says Professor Olivier Gaide, chief physician with the Service of Dermatology and Venereology at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). A broad study published in 2018 in The British Journal of Dermatology showed that the risk of severe depression was 63% higher in individuals suffering with acne than those without. This link was especially present in patientsdiagnosedless than one year earlier then subsided with time. “It’s important for young people with moderate to severe forms of the disease to receive support,” the professor says. “You can do something about acne. Acne can be treated effectively and with treatments that are now well known.”

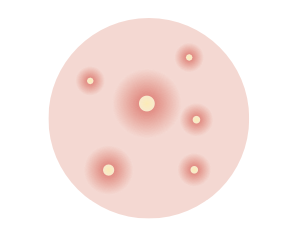

Acne most often starts at puberty, i.e., between the ages of 12 and 18, but rarely lasts into a person’s 20s. The hormonal changes going on during this period, as well as certain hereditary predispositions, lead to increased production of sebum, a film of fat secreted by skin glands known as “sebaceous” glands. Sebum is supposed to move up the hair follicle via a small canal, then up the pore to the surface of the skin. However, if too much sebum is secreted, or it is too thick, and the multiplication of cells (known as hyperkeratinisation) occurs, the duct can become clogged, forming a blackhead (open comedone) or a whitehead (closed comedone). This often affects the face, but acne can also appear on the back and upper torso

if conditions are met for a bacterial infection to occur. On the skin, the bacterium Cutibacterium acnes, normally present in very small quantities, develops and causes inflammatory lesions, ranging from small red spots (moderate forms) to large cysts (severe forms). “The treatment then targets the bacteria to suppress inflammation and prevent scarring,” Olivier Gaide says.

In the fight against the bacterium Cutibacterium acnes and the inflammation it causes, a family of molecules is proving to be almost miraculous: retinoids.

“They’re now the basis of most acne treatments,” the CHUV professor says. They are reimbursed by health insurance and are generally administered topically. In cases of severe acne, retinoids are ingested and pass into the bloodstream. The antiseptic benzoyl peroxide can also be used for moderate forms of acne thanks to its antimicrobial, anti-seborrhoeic and comedolytic effects. The product helps to slow down the reproduction of oils on the skin and eliminate blackheads. Laurence Feldmeyer, Senior Physician at the University Hospital of Bern, uses this type of treatment. In 2020, the dermatologist participated in drawing up the Derma Swiss acne guidelines, which specify that the use of antibiotics must remain limited, “so as not to encourage antibiotic resistance,” but cannot be avoided in certain cases.

“The retinoid family has an almost magical effect on acne,” Olivier Gaide says. “Unfortunately, its benefits are debated, mainly due to two controversies. First, the teratogenic effect of the drugs, i.e. they can cause congenital malformations. Second, these products have been reported to cause depression.” However, the chief physician offers reassurance,

“When they were first marketed, these products were prescribed in large doses. Today, they are prescribed in smaller amounts and in taking a much more targeted approach, according to the patient’s condition. The medical profession has gained a much better understanding of how acne works in the last ten years or so.” For example, one French study in 2020 showed the positive effects of the GATA6 protein, whose expression can be increased by retinoids. In the daily newspaper Le Temps, Bénédicte Oulès, a researcher from the skin biology laboratory at Institut Cochin in Paris and co-author of the study, explains that the protein helps to prevent the hyperkeratinisation, which is responsible for the formation of comedones. This limits the production of lipids by the sebaceous glands and has anti-inflammatory action.

“The teratogenic effect of retinoids is now taken seriously in consultations,” Olivier Gaide says. “We discuss whether a woman is trying to get pregnant or takes contraception. But recent research shows no relation with depression. The risks of depression linked to the disease itself in young people with untreated severe acne are much higher than the side effects of this category of drugs.”

Laurence Feldmeyer says that she is careful, keeping a close eye out for any signs of depression. “However, in most cases, the opposite is true. Young people feel much better in their skin after effective retinoid treatment for their acne than they did before.”

In young women, a hormonal evaluation can be carried out with a doctor, as excessive androgens can promote acne outbreaks. “It is then advisable to investigate the cause with a gynaecologist so that conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome can be ruled out,” Olivier Gaide explains. Oral contraception should also be discussed with women prone to acne. “Contraceptive pills that contain both oestrogen and progesterone generally improve acne but can have undesirable effects.”

For boys, dermatologists at the CHUV, as well as the expert committee behind the Derma Swiss guidelines, which included Laurence Feldmeyer, note that taking excessive supplements can have a negative effect. “Body worship among teens is more prevalent than it was 10 years ago,” Olivier Gaide says. “Some of them are into bodybuilding and take protein extracts, or even steroids similar to doping. Some don’t dare talk to us about it. But these products act on hormones and can aggravate or even cause acne.” And again, young people need to deconstruct the almost unrealistic images of men’s bodies on social media and big Hollywood films. /

When the spots returned to her forehead and chin, Fanny, 28, admits that it became a “fixation”. “I felt it was all anyone could see on my face.” Acne in the form of red, purulent cysts, which she had experienced between ages 13 and 14, was certainly “difficult enough at that time of life”, but most of her peers also had acne at school. “Acne is a different story in adulthood, because it’s much less common in the people around you. And, because it seems more abnormal than during adolescence, everyone has their own advice on how to get rid of it, always reminding us about our condition.”

The young woman ended up seeing a specialist.

“The dermatologist was quick to make the connection with the fact that she had stopped taking oral contraception less than a year earlier. Due to hormones, the pill had made my acne disappear for more than 10 years. But because I didn’t want to go back on the pill, we managed to remedy the problem with a fairly light treatment: oral medication for three months and creams applied daily on an ongoing basis. I only had one relapse last summer, probably caused by the sun.”

Persistent juvenile acne, as in Fanny’s case, is one of the most common forms of the disease, especially for people in their 20s, says Olivier Gaide of the CHUV’s Service of Dermatology. “Some people who experienced relatively mild acne in their teens didn’t need to seek medical help at the time. Then they end up coping with a disease and going to see a doctor. The doctor can prescribe treatments similar to those for acne occurring at puberty (see the main article on this subject), with the same positive results as for younger patients.”

Disrupted hormone levels can also explain adult acne. In these cases, the reason for this change must be eliminated, insofar as possible and by talking to the patient. “For example, we recommend stopping the anabolic steroids that some men take to increase muscle mass. In women, the cause could be a pro-androgen pill, which should be changed.” The CHUV professor cites another specific case, when people take hormones as part of a gender transition. “Patients want to look more manly, to reduce the size of their breasts, and to increase muscle mass and hair growth.

But, unfortunately, one of the negative aspects is that men, because of androgens, suffer from acne more than women. So we try to support them as best we can, especially by adapting their hormone dosage.”

Non-hormonal drugs, such as anti-tuberculosis drugs or corticosteroids, can also induce lesions resembling acne.

Finally, a condition known as “adult female acne” can occur in patients who never suffered from the disease before. “These women are generally very slim, with low levels of oestrogen in their bodies, as these hormones are stored in fat. Due to stress, the level of the famous androgens will, conversely, increase. And this imbalance will encourage the appearance of lesions on the chin, for example.” In such cases, the Service of Dermatology will suggest trying to reduce stress as much as possible and use a retinoid-based treatment, “which is often the only effective medication.”

Dermatologist Laurence Feldmeyer advises against touching blackheads and blemishes. “Unless you’re having a peel performed on your doctor’s recommendation, in a professional cosmetic practice, it’s best to avoid pressing or scratching the lesions to prevent a worse infection and scarring.”

A paediatrician or a general practitioner can prescribe local treatments initially. Derma Swiss recommends that people suffering from severe forms should be referred to a specialist, as should anyone who does not respond adequately to basic treatments and those experiencing relapses.